Frederick City, September 29th [1862].

How different now is this peaceful valley grown in the short interval of time. And how sad. The thunder-clap of war has now rolled to the distance, leaving Nature slowly to recover from the paralyzation of its recent shock. It were not, perhaps, a smaller contrast, to note the difference in my condition, hope and prospects now, with two weeks ago. I was then hastening over this same road with thousands and thousands of others….I was full of life and vigor, and yet wondering if my fate might not be to have my bones become a part of the dust of the mountain….Now the campaign is ended. I had fondly hoped that I might so term the war. Maryland is free from the tread of Rebel hosts and the Nation rejoices in a great victory, as it mourns over the countless dead. I am returning with many others, helpless, to the little city of Frederick, seeking tenderness and care.

Private Charles F. Johnson

9th NY, Hawkins Zouaves

Civil War period graffiti, names inscribed, penciled, or written in charcoal on walls, rocks, and windowsills, marks the paths that Confederate and Union soldiers followed through the Catoctin Mountain region. Silent tokens of the horror of civil war, the signatures also remind us that the grand armies, the corps, battalions, regiments, and companies were composed of individual human beings. The inscriptions served often as a forum for political opinion, a palate for artwork, or a simple attempt to be remembered. Mostly though, the graffiti filled the moments of boredom experienced by soldiers during the long periods of dull routine between battles.

Maryland Heights and Harpers Ferry – 1861

The journey began in 1861, shortly after the long-simmering disagreements between North and South dissolved into secession and war. Massachusetts regiments were among the first to mobilize. The 13th Massachusetts (Rifle) Regiment, including the 101 men of Company K from the Marlborough area, marched out of Boston the last week of July, 1861. In a letter submitted to the Roxbury City Gazette on August 1, a writer noted, “The regiment was well armed with Enfield muskets….The destination of the regiment is supposed to be Harpers Ferry.” The state-of-the-art rifled muskets would prove to be an advantage for long-range accuracy, over the “smoothbore” standards until recently manufactured in the Harpers Ferry federal armory.

Finally arriving in late August at the southern tip of Washington County, Maryland, across the Potomac River from Harpers Ferry, the men of the 13th Mass. skirmished on and off with Confederates on the Virginia side of the river. But as the days stretched – boredom set in: “Life is dull here – nothing to do, and plenty of it,” observed another writer to the Gazette on August 29. Stationed on the rocky cliffs of Maryland Heights overlooking Harpers Ferry, the sharpshooting “Rifles” protected the important C&O Canal, proving their superiority over the smoothbore.

As their stay lengthened into October, opportunities for idleness grew. Crouched among the boulders on the Heights, a number of the soldiers of the 13th Mass, Co. K carved their signatures. Despite the fading effects of weathering a few are still legible, particularly those of Private George H. Gates and Gardner R. Parker. Private Gates, a Cambridge

N.Y. native, chose an iron-stained flat rock to leave his mark. Gates mustered into service with the 13th Mass on July 16, 1861 at the age of 28. At that time, Gates’ occupation as a brewer filled his days. Mustered out on August 1, 1864, the brewer-turned-rifleman returned to New York to live in Brooklyn. Gardner Revere Parker left his name deeply

inscribed on a rock above Gates’ name. Born in Lowell, Massachusetts, Private Parker was 24 years old when he enlisted in July 1861.5 Although he worked as a freight man on the Boston and Albany Railroad before the war, his talent as a stone carver implies some knowledge of the trade. On December 13, 1862, at Fredericksburg, Virginia, a bullet blew off Parker’s right thumb and ended his carving days. With his right leg also wounded, Private Parker headed for the hospital. It is said that Gardner Parker, tiring of his confinement in army hospitals, finally skedaddled for Worcester: “Parker wanted out for good – he had fought until wounded, two of his brothers had been killed, and a third had been wounded. The army forgave him and granted him an honorable discharge.”

Out of the Frying Pan, Into the Fire – 1862

The town of Harpers Ferry suffered early from massive destruction, the result of constant wrangling for control of the important border location and B&O Railroad supply route. Within the first months of the war, one or the other army had burned the federal armory, Herr’s flourmill, and the railroad bridge across the Potomac. Many of the houses, abandoned by the town’s frightened civilian population, stood empty, their contents removed by the owners or looted by strangers.

By the end of 1861, the 13th Mass. had marched south into Virginia, and new Union faces were arriving in the Harpers Ferry area. Baxter’s Fire Zouaves, the 72nd Regiment, Pennsylvania Volunteers, had called their enrollment from the various firehouses of the Philadelphia area:

ATTENTION PHILADELPHIA FIREMEN – Colonel Baxter’s Philadelphia Fire Zouaves, Company G, now forming in the western part of the city, will be mustered in immediately. Twenty-five more men wanted. Recruiting Offices, 318 Chestnut Street, upstairs, and Sixteenth St. above Callowhill.

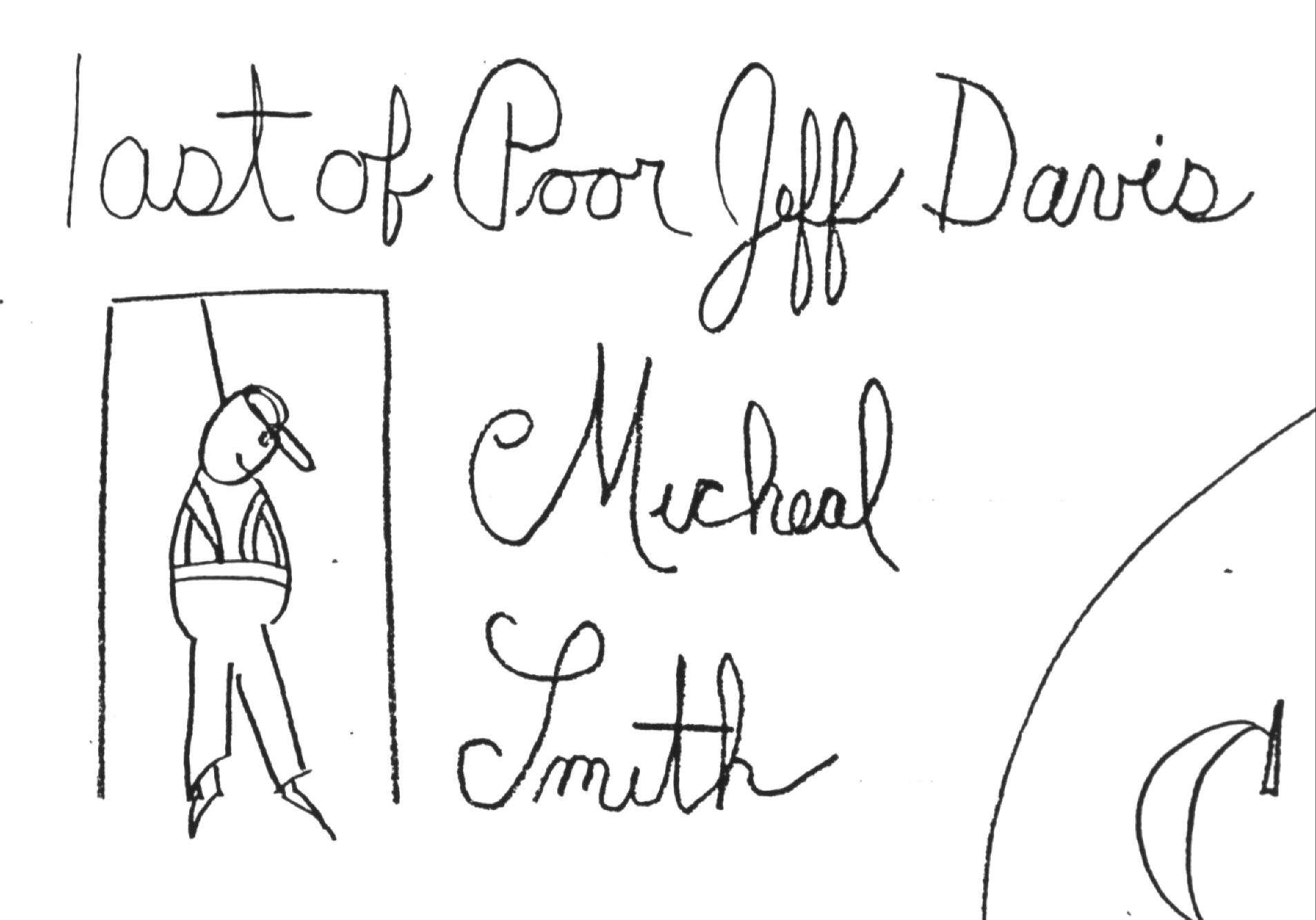

E.G. Roussell, V. Hagerman, C. McCarty

After initial training in Poolesville, Maryland, Baxter’s Zouaves stayed in Harpers Ferry from January through February 1862. For two months, the boys of Company G cooled their heels in the abandoned homes of Harpers Ferry. In Frederick A. Roeder’s store on Potomac Street, 1st Lt. Victor Hagerman and eight of his enlisted men filled their empty hours by decorating the plaster walls. The firemen of Philadelphia left messages for the Confederacy, perhaps the most graphic drawn by Private Michael Smith showing the “last of Poor Jeff Davis.” Smith was 19 years old when he enrolled and listed his occupation as “Gentleman.” Lt. Hagerman, perhaps in honor of their French Zouave association, wrote after his name “de Maulhouse France, Mora aux truhels,” perhaps translated as, “of Mulhouse France, death to traitors.”

Someone among the group was an artist, gracing the second floor walls with portraits of a man and woman, “Jeff Davis” on a horse, and an elegant rendition of the American flag. Another simply wrote in large letters across the wall, “LEAP FROG LEAP TO HELL.” Other signers of the garret walls from Company G included Pvt./Corp Benjamin Harris, who declared “Death to Traitors,” Pvt. James Dougherty, Pvt. James Starr, Pvt. Samuel Floyd, Pvt. James Breckenridge, Pvt. Josiah Dicsey (listed as Isaiah Dixey in the records) and Pvt. John Henk. Private Henk was a machinist when he enrolled at age 19. He re-enlisted in February 1864 at Stevensburg, Virginia, transferred to the 183rd Regiment, and promoted to Corporal.

The 72nd Regiment Pennsylvania Volunteers were among the mass of over 100,000 Union troops that came to the Antietam battlefield at Sharpsburg, Maryland in September 1862. Baxter’s firemen of Philadelphia were attached to Sedgwick’s 2nd Division, O. O. Howard’s 2nd Brigade, known as the Philadelphia Brigade. Moving through the West Woods during the morning phase of the battle, the enfilade of McLaws’ Confederates devastated the Brigade. Although the Philadelphia Brigade, made up of only four Pennsylvania regiments, had the highest number of casualties resulting from the Antietam battle, remarkably, none of the signatories of the walls of Roeder’s store in Harpers Ferry was among those killed. However, Pvt. James Starr later lost an arm from a wound inflicted at Antietam, and both Pvt. Dixey and Lt. Hagerman were discharged after the battle due to injuries.

The Maryland Campaign – 1862

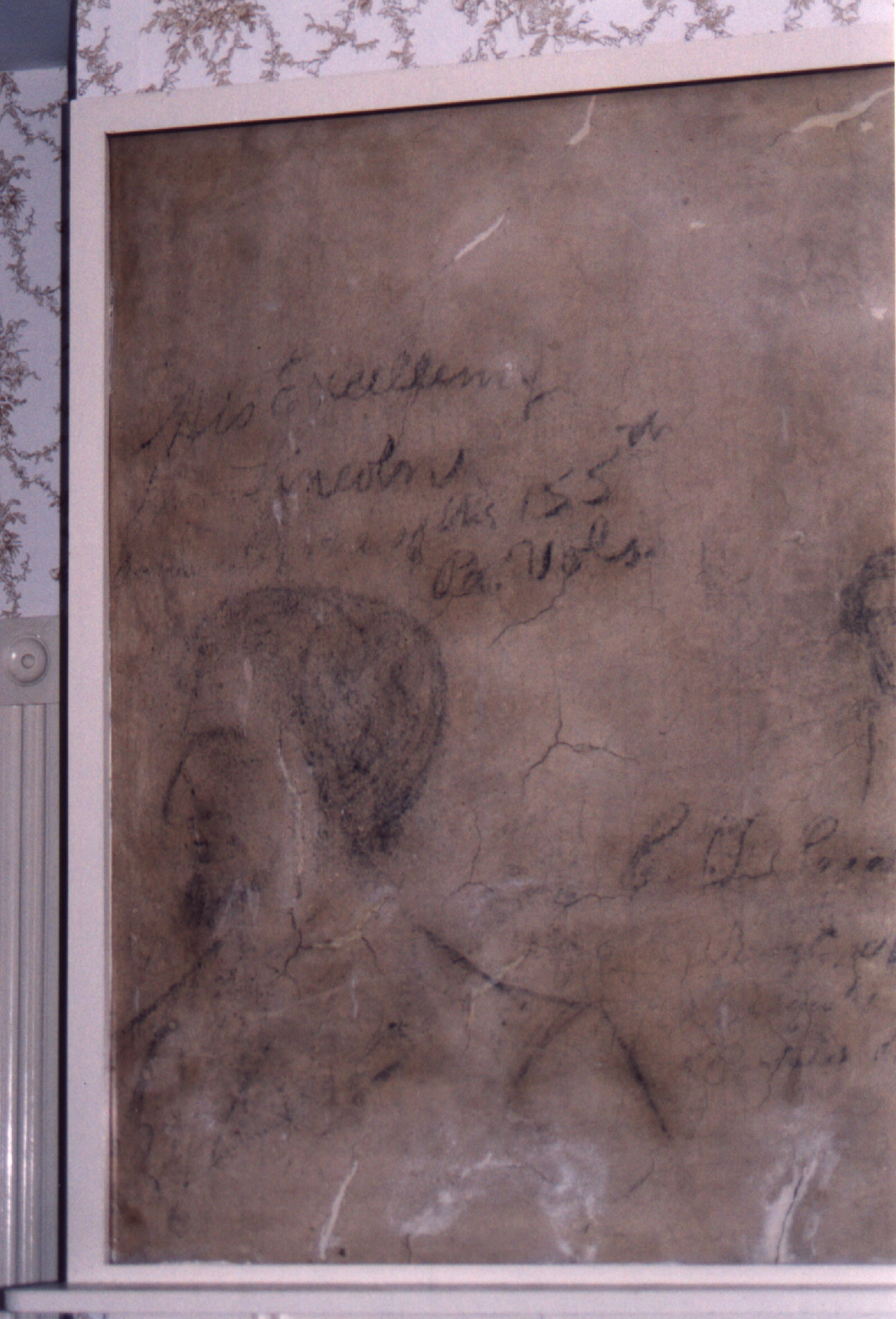

As the war marched on through the summer months of 1862, events began to unfold that would culminate in the September battle of Antietam, known as the bloodiest single-day battle of the Civil War. Late in August, General Robert E. Lee commenced the Maryland Campaign, crossing the Potomac River south of Frederick. As their route led through Urbana, Maryland, the cavalry of Longstreet’s Corps under the command of Major General JEB Stuart stopped several nights at the former Landon Military Academy, lately a Female Seminary. Reported to be the location of the Sabers and Roses Ball, hosted by Stuart on September 8, 1862, the expansive building sheltered as many as one hundred Confederate soldiers. According to the Union troops that followed several days later, “…they had written their autographs, and many unpatriotic inscriptions, with burnt sticks, on the beautifully, white-plastered walls.” Not to be outdone, the men of the 155th Regiment Pennsylvania Volunteers Co. E left their own inscriptions, gracing the wall above the parlor mantel with the likeness of “His Excellency Abraham Lincoln.” The men of the regiment who were there recalled that, “Private McKenna, of Company ‘E,’ especially distinguished himself on this occasion as a lightning artist, and was given three cheers by the comrades who witnessed his performance, and unanimously voted Regimental artist.”

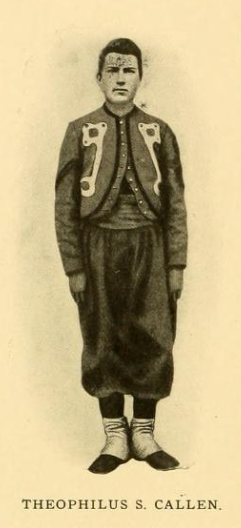

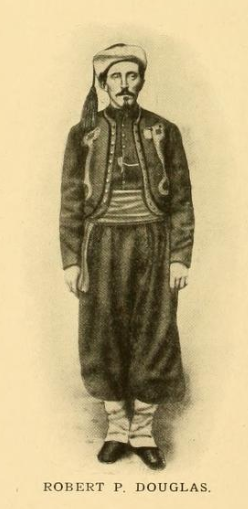

The men of the 155th whose names were immortalized on the walls of what is now called Landon House in Urbana were stragglers, exhausted by their pursuit of the Confederate army through Maryland. Among them were Sergeant John M. Lancaster, Private Theophilus S. Callen, Corporal Newell D. Loutseneiser, Corporal Thomas P. Tomer, and Privates James I. O’Neill, Robert P. Douglass, Hugh Leonard, James Finnegan, and John Crookham. All, like Private Charles F. McKenna, were members of Company E, except Finnegan of Co. D, mustered into service less than one month earlier from Allegheny County in western Pennsylvania. Within weeks of their recruitment, these soldiers found themselves first on the battleground of the South Mountain passes, and three days later approaching Antietam. Despite their lack of training, all of these men survived their first battles. But in 1863, Corporal Tomer was wounded at Gettysburg. Tomer remained in the Union army as a member of the Veteran Reserve Corps until 1865. During the Wilderness battle of May 5, 1864 in Virginia, Private O’Neill was wounded. He too finished his service in the Veteran Reserve. Corporal Loutsenheiser was also wounded at the Wilderness, but died several days later and was buried in the National Cemetery at Alexandria, Virginia in grave No. 1,922.

…Sergeant Lancaster and Privates McKenna, Hipsley and Douglass, of Company E, under the fire of the enemy on the advanced skirmish line, rescued and carried in from the front the body of Private Theophilus S. Callen, of the same company, who had been killed on vidette outpost just before daylight that morning.As they dug their friend’s grave beneath a peach tree, reward for their bravery came with the discovery of a Confederate stash of silverware, “but no gold or silver coins.” Private Charles F. McKenna, lightning artist and brave comrade, survived the war and went on to become a lawyer in Pittsburg. President Theodore Roosevelt later appointed him to the position of Federal Judge of Puerto Rico. Robert Douglas became the manager of the Eliza Furnace Works.

Home is Where the Heart Is

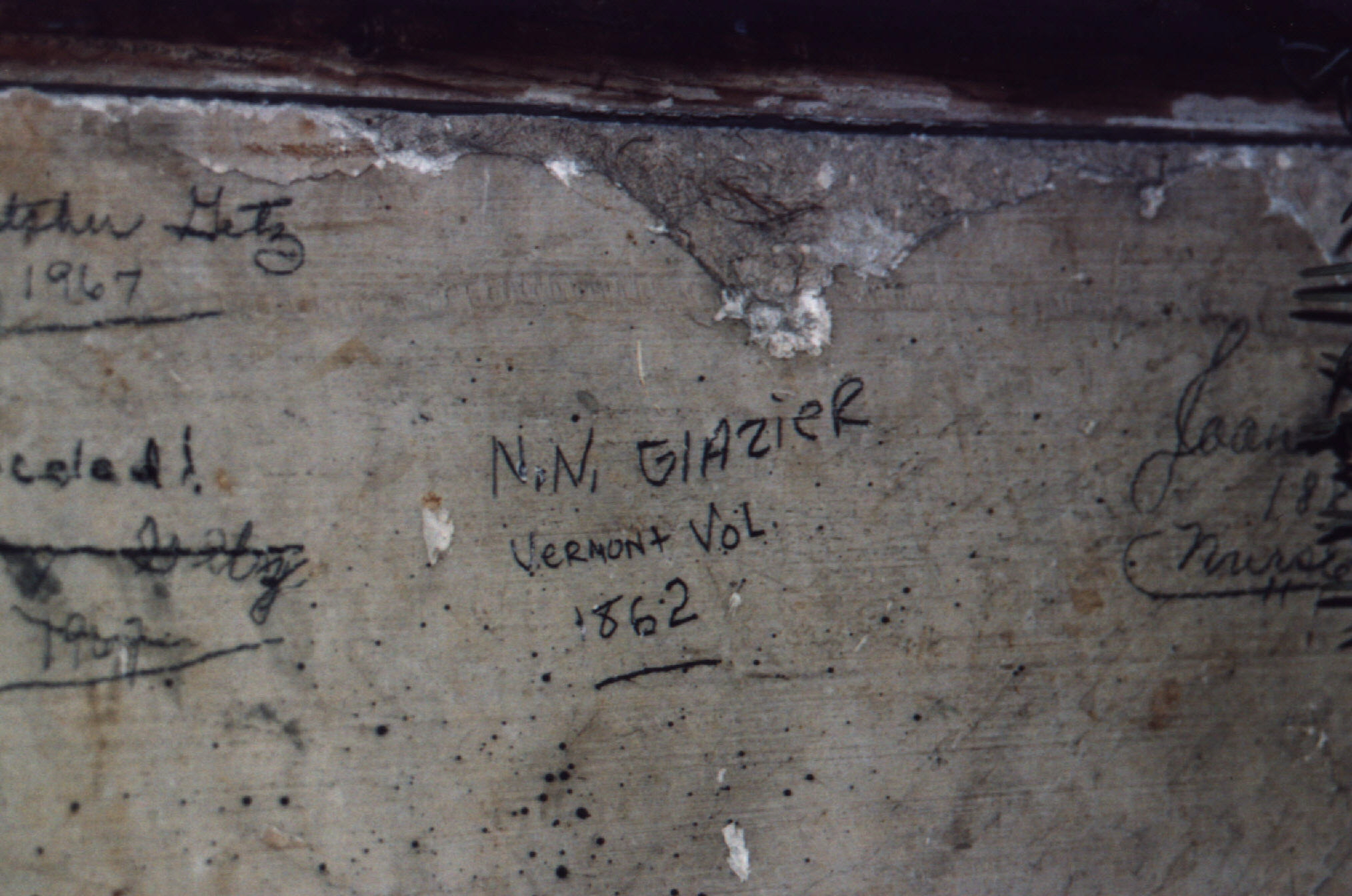

Just one month prior to the Antietam battle, Amherst College sophomore Nelson Newton Glazier, enlisted in the 11th Regiment, Vermont Volunteers, Co. G. Private Glazier traveled with his company in September 1862 to Fort Lincoln, and later Fort Slocum, for “Duty in the Defences [sic] of Washington, D.C.” The skills in artillery demonstrated by the men earned the regiment a change in designation to 1st Heavy Artillery in December 1862. However, Newton Glazier’s education no-doubt influenced his position as clerk in the Adjutant’s office. In September 1862, while his compatriots labored at the construction of the Washington forts, Glazier attended to his clerks’ duties, noting in a letter: “It is much pleasanter for me to remain in camp than it would be to go out and aid in throwing up these works; you know I am not so immoderately fond of work as many are.”

The 11th Regiment remained at the Washington defensive forts through May of 1864 and did not participate in the Antietam battle of September 1862. Yet Newton Glazier’s signature, dated 1862, appears on the garret wall of the Moulder Building in the nearby Virginia town of Shepherdstown (now West Virginia). Although his letters do not mention a trip to Shepherdstown, Glazier’s duties in the Adjutants office included stints as courier to the other Washington forts, and perhaps as far as Shepherdstown during the long Union occupation following the September battle.

Throughout his time around Washington, N. N. Glazier rose through the ranks. In November 1863 he became 2nd Lieutenant of Company A and in January 1864 was elevated to 1st Lieutenant. Although spared the heavy labor of construction, and apparently relatively comfortable in his camp, Glazier complained of stomach illnesses often and grew increasingly homesick. While describing his camp in Maryland as “some four miles north of Washington, in a very pleasant country, healthy in locality,” still his heart longed for home: “No other place has half the attraction, no other place has so many holy associations, no other place is half so dear as my own Vermont.”

On the morning of May 12, 1864, Newton Glazier wrote from Fort Slemmer [Slocum?] near Washington, D.C.: “My Very Dear Father; We are expecting to leave tomorrow for the ‘Front’ – They are having an awful battle in Virginia – we expect to join Grant soon…I think Grant is determined to win or sacrifice the Army in the attempt.” Nine days later, Glazier wrote from Hospital B, 2nd Division, 6th Corps, Fredericksburg, Virginia:

My Dear Father – Early Thursday morning May 19 My left arm was struck by a piece of shell near the shoulder – amputation was necessary…I am thankful I am as well off as I am. O pray for the wounded & the Dying – I hope our cause will be victorious. I trust that the old Flag borne upward by Northern Prayers & borne onward by Northern blood will triumph yet – good bye – I am very weak.

N. N. Glazier

Having lost his arm from the wound at Spotsylvania, Lt. Glazier was honorably discharged from the Union army on September 3, 1864. In 1865, while he continued his college studies, Newton Glazier represented his hometown of Stratton in the Vermont legislature, and in 1869, he was ordained a Baptist minister. Rev. Glazier served a number of Vermont and Massachusetts congregations, recalled his great-niece, Maud C. Eaton, who noted:

The last fifteen years of his life as a retired pastor were spent with his blind sister, Czarina Abigail Glazier Williams, then 92 years of age, at Beatrice, Nebraska; Muscotah, Kansas; and Ashland, Nebraska. He died at Ashland, Nebraska in the fall of 1922 and was buried at Willow Creek Cemetery north of Prague, Nebraska.

The Eyes of General Lee – 1863

Early in the summer of 1863 General Robert E. Lee again decided to take the war into Northern territory. With his eye toward Pennsylvania, Lee led his army northward through Maryland behind the cover of the South Mountain and Catoctin Mountain ranges. For three days in July, the town of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania was the center of one of the war’s most pivotal battles. Unable to break the Union lines at Gettysburg, Lee’s hungry and bedraggled army retreated southward through two days of driving rain to the banks of the Potomac River. The swollen river forced the men to remain in Maryland, setting up their defenses in a line stretching from Funkstown to Downsville.

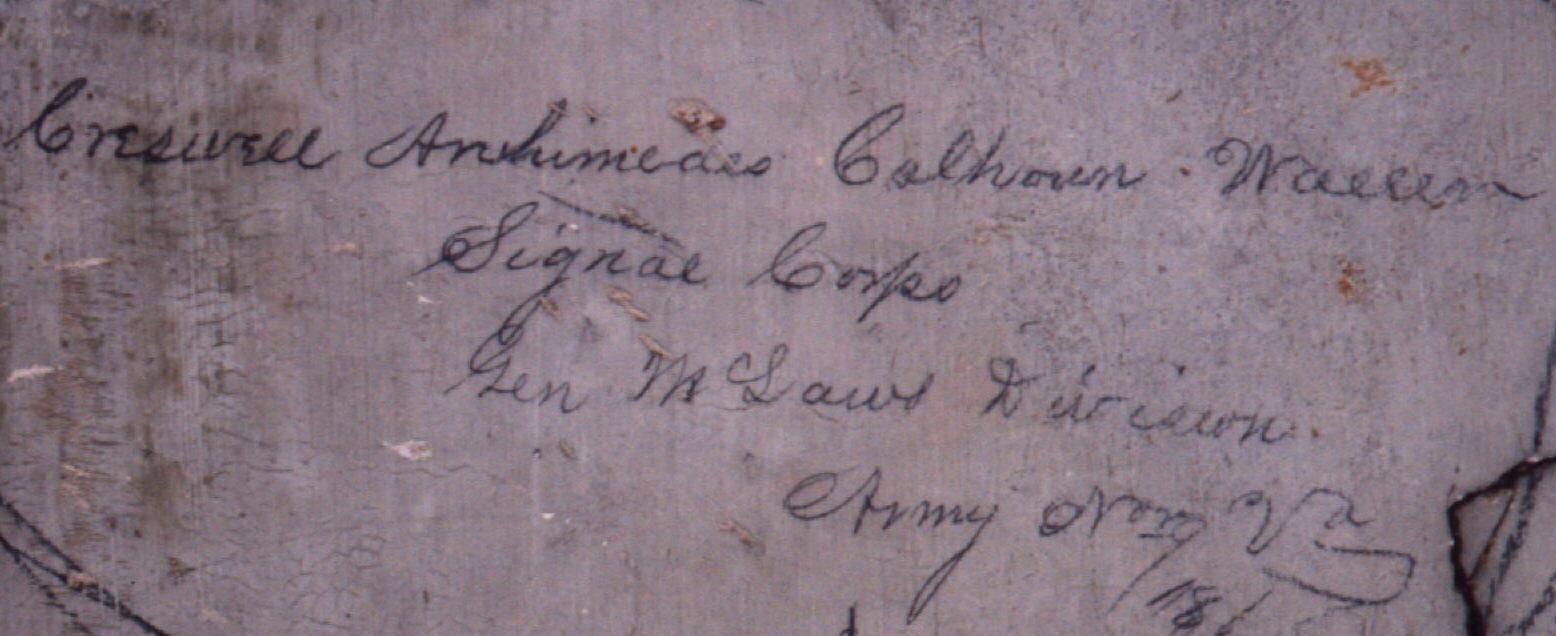

As both Union and Confederate armies had found over the previous year, a competent signal corps placed in strategic positions was an invaluable tool in “modern” warfare. The widely extended lines of the Confederates, trapped by the swollen Potomac, found advantage in their position using a widows walk on the roof of a manor house known as Linden Hall near Williamsport. The large house stood on a low hill surrounded by cultivated fields, providing an unobstructed view of three states: Maryland, Pennsylvania, and West Virginia. From this vantage point, the men of the Confederate Signal Corps assigned to General Longstreet’s 1st Corps provided information on the cautious movements of Meade’s pursuing Union army. Longstreet reported later, “…the command was put in camp on the best ground that could be found, and remained quiet until the 10th, when the enemy was reported to be advancing to meet us.”

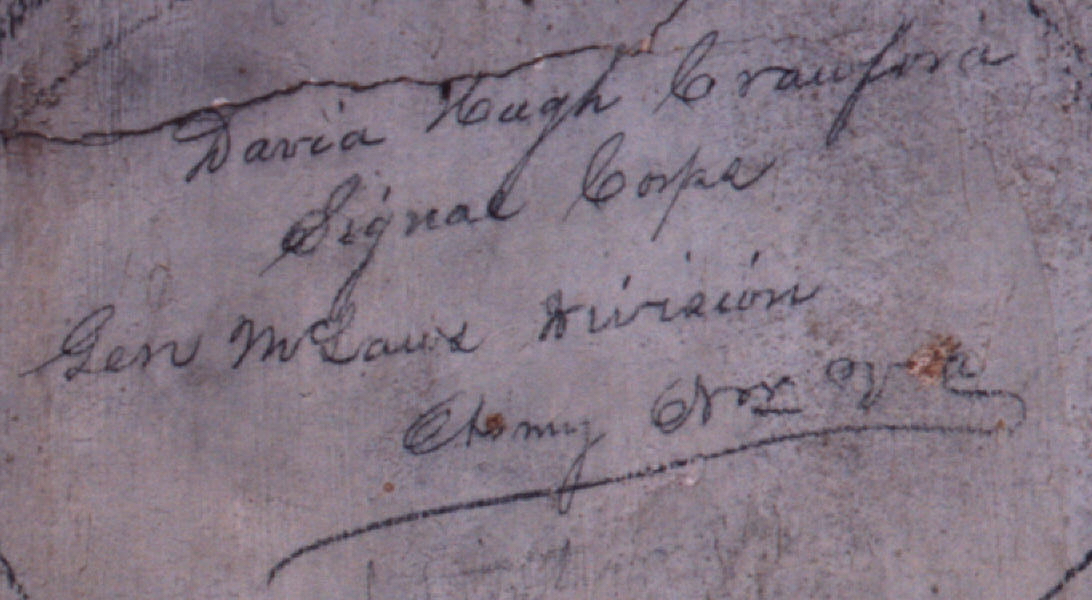

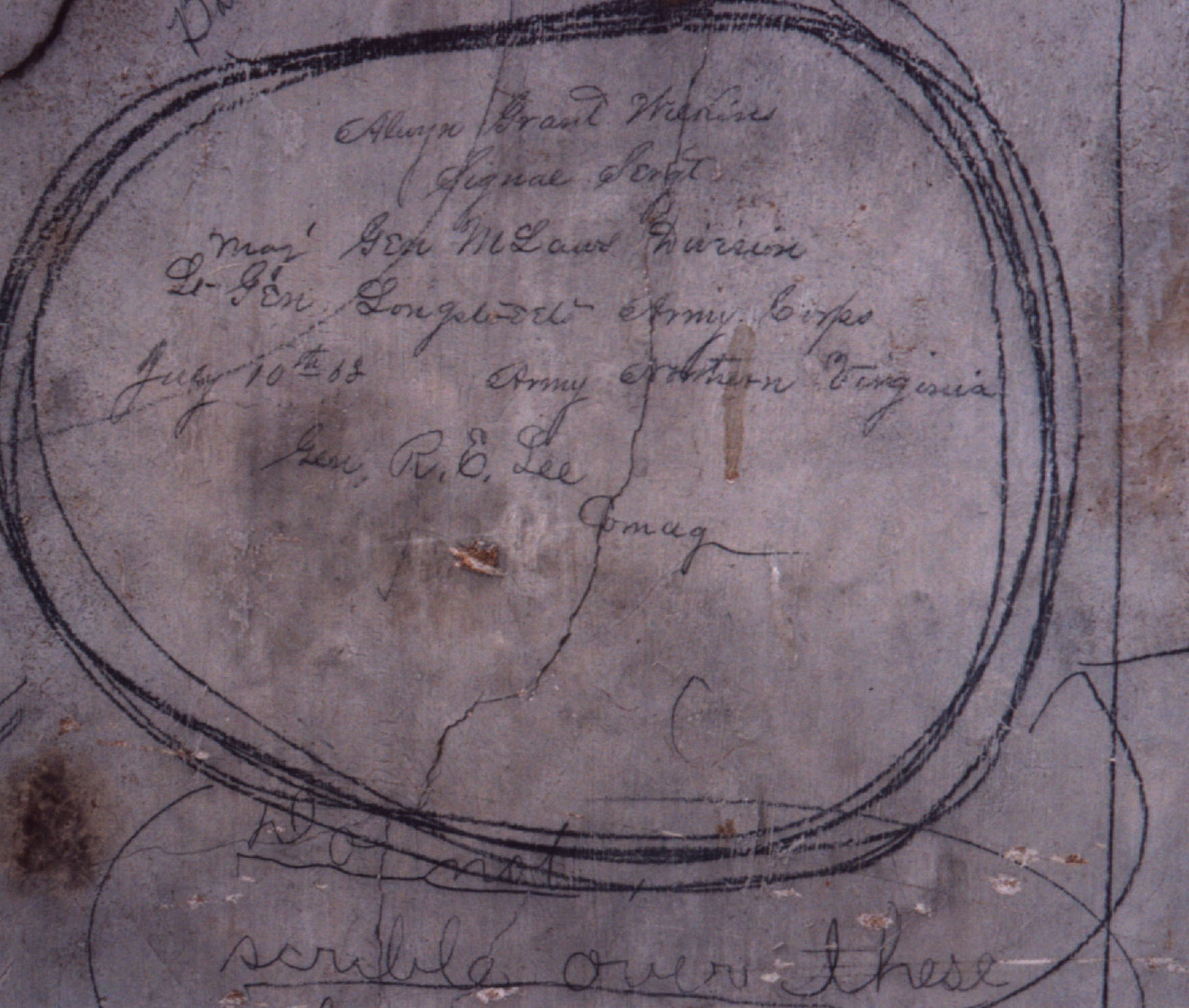

The signalmen who manned the rooftop post at Linden Hall found refuge during quiet moments in the cramped garret room. Penciled inscriptions on the plastered walls dated July 10, 1863, were probably written just prior to the sighting of the approaching Union cavalry. Although all written in the same hand, the inscriptions detail three South Carolina men, all from Gen. McLaw’s Division, Army of Northern Virginia: David Hugh Crawford, Alwryn Grant Wilkins, and Creswell Archimedes Calhoun Waller.

One might speculate that Wilkins wrote the inscriptions, his signature containing the most detailed information.

The Confederate Signal Corps, established by the Confederate Congress on May 29, 1862, was under the command of Major William Norris, a native of Reisterstown, Maryland. Soldiers who could read and write were recruited from various regiments for service in the corps. The activities of the Confederate Signal Corps remain largely shrouded in mystery; however, an 1888 article in the Southern Historical Society Papers described its organization:

The Signal Corps, as organized, consisted of one Major Commanding, ten Captains, ten first and ten second-class Lieutenants and twenty Sergeants—there were no privates, as men were detailed from the line of the army whenever wanted, and when their services were no longer required they returned to their respective commands.

David Hugh Crawford was detailed to the Signal Corps from the 15th Regiment, South Carolina Infantry, Co. A. Records indicate that Crawford was a 16-year-old student when he enlisted at

Columbia, South Carolina. Signal Sgt. Wilkins described his occupation as “engineer and student” when he mustered into service. Although it is unknown what regiment he belonged to initially, in 1864 he transferred to the Army of Tennessee and was stationed at Kinston, North Carolina. Creswell A.C. Waller joined the ranks of Co. F in the 2nd Infantry Regiment of South Carolina prior to his detachment to the signal corps.

The men of the signal corps suffered the unfortunate misconception among fellow soldiers of serving as non-combatants in “‘bomb-proof’ positions.” In reality signalmen found themselves in some of the most dangerous and unprotected positions possible. Located on the highest and often the most visible vantage points, they were regular targets of sniper fire. Yet despite the danger, the corps steadfastly fulfilled their duty:

To comrades true, far, far away, Who watch with anxious eye, These secret signs an import bear When waved against the sky. As quick as thought, as swift as light, Those airy symbols there, Are caught and read from The Bonnie White Flag That Bears The Crimson Square.

On honoring the men of the Confederate Signal Corps in 1897, A.W. Taft noted, “…what greater compliment can be paid to any man than to say of him that he had been selected for his intelligence and reliability from the ranks of the Confederate army, whose merits have won the admiration of all nations?”

Remembrance and Reunion – Antietam’s Dunker Church

America’s Civil War ended in the spring of 1865, but for the surviving veterans the brotherhood born on the battlefield remained with them for the rest of their lives. Reunion encampments became a common sight on former battlefields as the men gathered to commemorate battles and honor fallen comrades. These reunions had a profound impact on many of the communities around the battlefields as the War Department purchased the hallowed ground and thriving “tourist” businesses grew.

Remarkably, the Antietam Battlefield changed little in the decades after the war. Despite the fact that the land remained in private ownership, the region’s robust agricultural economy helped to preserve the farms and the Sharpsburg community much as it had appeared during the 1860s. The Dunker Church that stood at the center of the bloody battle, also remained little changed through the nineteenth century. Standing alone at the edge of the West Woods, the little church was perhaps the most recognizable landmark from the battle for returning veterans.

Through the 1880s and 1890s and into the first decades of the twentieth century, monuments to the fallen grew on the fields of Antietam. The New York monument, among the largest on the field, stood near the old Dunker Church. It was probably during one of the veteran’s reunions that members of several New York regiments carved their names on the outside window sills of the Dunker Church. Henry Winters, a Broome County, New York native with the 89th NY Infantry, Co. H, participated in the afternoon phase of the daylong Antietam battle under the command of General Ambrose Burnside. Crossing the Antietam Creek at Snavely’s Ford, just behind the Hawkin’s Zouaves, the 89th New York faced the perfectly timed arrival of Confederate General A.P. Hill’s Division from Harpers Ferry. Winters’ regiment had been as far away from the Dunker Church as any could be on the battlefield, and yet it was there that he and several others chose to leave their mark.

In 1921, a windstorm demolished the old Dunker Church, by then used as a gas station and general store. The remnants of the building, including six of the original eight window sills, were placed in storage by an astute Sharpsburg resident. In 1961, the National Park Service reconstructed the church using 3,000 of the original bricks and 17,000 new bricks to match, returning the carved sills to their historical location.

Vandalism, art, or icon, graffiti means many things to many people. Fortunately, for those interested in the men who served during America’s Civil War, the graffiti they left behind provides a window into the soldier’s lives, both ordinary and extraordinary. Found in houses, courthouses, churches, and other buildings and sites throughout much of Maryland and Virginia, as well as other states that saw action during the Civil War, the preservation of these inscriptions provides an important layer of personal history associated with America’s war.

Stories in Focus