Over one hundred unique, beautifully carved tombstones are scattered in church and family cemeteries along the border between Maryland’s Carroll and Frederick Counties. They were created in the first half of the nineteenth century by an African American stonecutter named Sebastian “Boss” Hammond. Time and weather have been very kind to them, and many look as if they were erected only yesterday. They are the legacy that Hammond left throughout the area where he lived for more than ninety years. The life of this craftsman and farmer is as intriguing as his work.

Sebastian Hammond, also known as Boss Hammond, was born enslaved sometime between 1795 and 1804, probably on a large farm belonging to one of the Hammonds of Liberty District, Frederick County, Maryland. Liberty was home to many large landowners who moved from the tidewater region of Maryland during the latter half of the eighteenth century, taking along enslaved people to work their vast fields. Some of these families were “land-rich, cash-poor;” they owned thousands of acres and some enslaved people but not much else. Their homes were usually plain and functional, unlike the elegant establishments of those Hammonds, Ridgelys, and Carrolls who lived near Baltimore and Annapolis. In 1799, Upton Hammond married his cousin, Arianna Hammond, both of whom had grown up in Liberty District. Arianna already owned about 500 acres at the time of her marriage, a gift from her father, John. Upton anticipated inheriting land from his father, Vachel, also a large landowner. The young couple probably held enslaved people or were given them when they married. One or perhaps both of Boss Hammond’s parents may have been enslaved by the couple. Boss was definitely part of Ariana’s property in 1824 when he was roughly twenty years old. Because a child followed the “condition” of the mother, there is no doubt that Boss’ mother was enslaved herself. In 1785, a Thomas Hammond of Frederick County manumitted his bondsman “Boss,” but whether this man was the father of “young” Boss will probably remain a mystery. Hammond genealogy is very difficult to trace on both the African American and white sides because the same given names were used repeatedly in different branches of the family through several generations.

During the early years, Boss Hammond probably spent much of his time working in his enslaver’s fields and with livestock. The lifestyle of the white Hammonds in Frederick County was relatively simple and the skills Boss demonstrated in later life were consistent with early years spent farming rather than as a house servant. Central Maryland farmers with large acreage slowly abandoned tobacco growing during the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries and concentrated instead on cereal crops. Wheat, oats, rye, and corn did not deplete the soil as badly as tobacco, and raising these crops did not require a large labor force except during planting and harvest time. Boss probably gained some experience raising tobacco as a youth because he grew it on his own farm in later years. In addition to doing farm work, he may have been hired out by his enslaver to learn trades from nearby craftsmen and afterwards brought back to the farm to apply what he learned. This was a common practice among enslavers. There were times, especially in the winter months, when farm work was slack and boys or men could be spared for

other things. Hiring out enslaved people also brought in cash to an enslaver’s pockets. The majority of Frederick farms had fewer than twenty enslaved men, women, and children, so anyone with a range of skills would have been valuable when the work force was small.

Arianna Hammond filed a manumission for Boss in 1824 which promised him freedom on January 8,1844. She estimated he would be approximately forty years by that time. When she filed the manumission, Arianna was a widow responsible for several children, hundreds of acres of property, and a number of enslaved people. No doubt she believed she was ensuring the loyalty and assistance of Boss by releasing him from bondage, albeit twenty years in the future. She had numerous relatives living in Liberty District including Upton’s younger brother, Colonel Thomas Hammond, a widower with much land of his own. Undoubtedly they helped her in many ways during this period. Various records show Col. Hammond was closely associated with her and her children for many years following Upton’s death. Arianna Hammond married John Walker sometime after filing Boss’s manumission, but by 1830 she was a widow once again. Colonel Hammond purchased Boss that year at the sale of John Walker’s estate and Boss remained the Colonel’s property until 1839. There is no indication Boss was ever enslaved by anyone outside the extended Hammond family, a fact which may explain his use of the family’s surname.

The earliest evidence that Boss Hammond had acquired stone carving skills comes from a memorial for John Walker originally erected in the Hammond family cemetery at “Black Castle,” east of Libertytown. Walker’s (now broken) headstone now stands in Fairmount Cemetery beside other headstones removed from “Black Castle” many years ago. Boss probably carved it in late 1830, close to the time of Walker’s death. It has all of his trademark decorative elements plus one never seen afterward, but the lettering and letter spacing are decidedly inferior to most of his other work. Boss was still struggling with certain aspects of his carving although he had mastered many other stonecutting skills. A number of his tombstones with dates prior to 1830 are beautifully lettered, these, however, were likely produced sometime after 1830 and backdated. Memorials frequently were erected many months or years after a person’s death.

The name of Hammond’s carving mentor is a mystery, but three distinctive headstones from different cemeteries along the Carroll-Frederick border appear to be his creations. The initials “J.N.” were prominently inscribed on the lower part of two tombstones—perhaps to identify the maker. Families named Nusbaum, Naill, Nicodemus, and Norris lived in the vicinity during the early nineteenth century, but so far “J.N.” has remained elusive. This carver used rock native to the area, created a border around his stones, and decorated them with scroll motifs, all characteristics he shared with Hammond. He employed several lettering styles, including script, and often slanted entire lines of text either forward or backward. His chiseling was generally shallow, so nearly two centuries of weathering have left his stones more difficult to read than Hammond’s. Based on the variety and sophistication of his lettering, it is probably fair to assume this craftsman was literate.

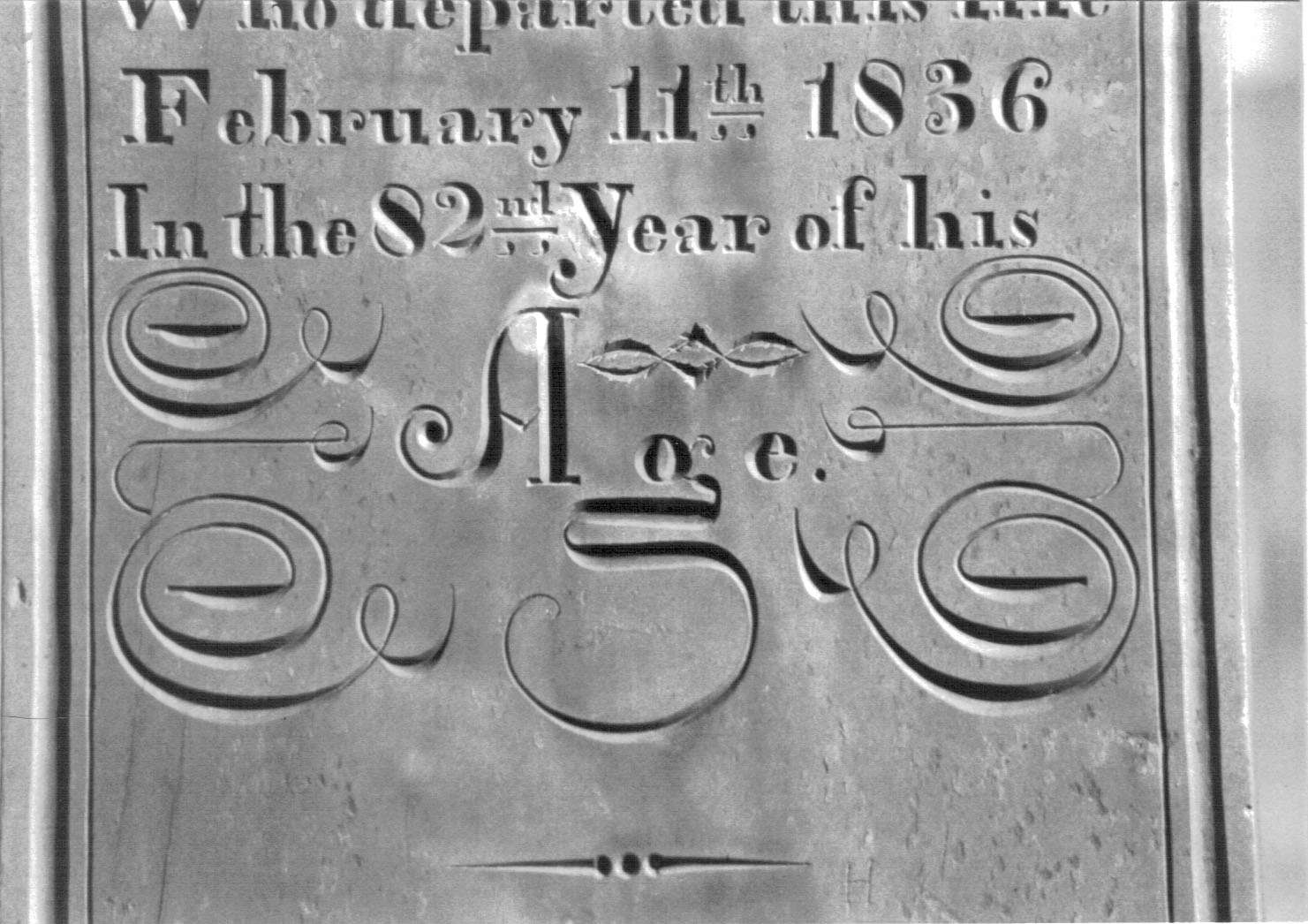

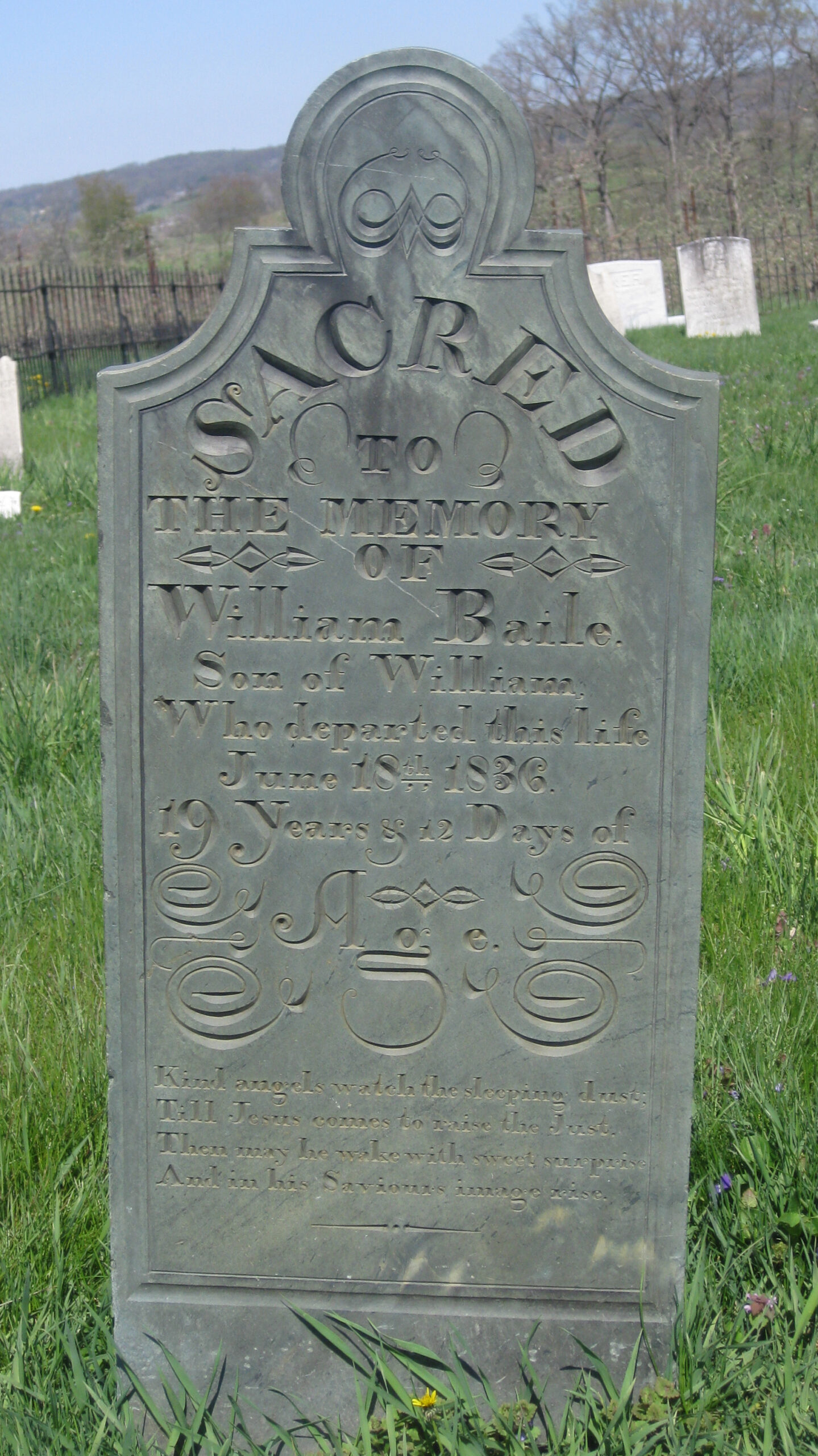

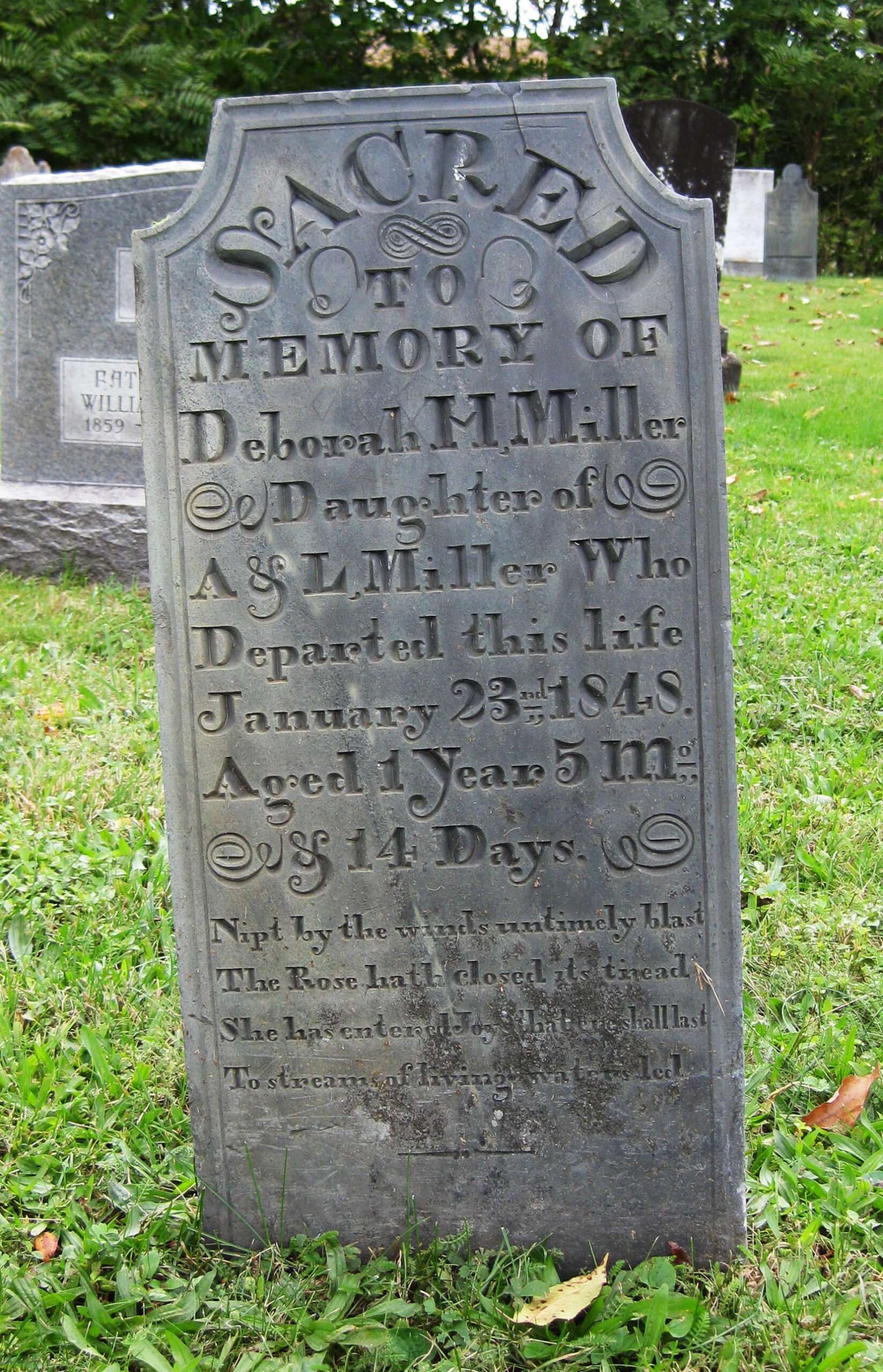

Boss Hammond’s work is easy to recognize. He produced stones of two basic shapes and used one style of lettering throughout his long career as a carver. His obituary in the Democratic Advocate of Westminster, Carroll County, says “He learned to cut letters on tombstones, and although he did not know one letter from another, he could cut all kinds of fancy work from a copy correctly.” In spite of his inability to read or write, Hammond always produced stones on which words were spelled correctly and punctuation was properly applied. Even on large stones with eight or ten lines of verse he was accurate. He did not attempt things he had not mastered and wisely stuck to what he knew. Although it is hard to believe he was illiterate when looking at his work, there are instances where other illiterate individuals have mastered skills such as typesetting. Perhaps he received help from a nearby schoolteacher or other educated neighbor when he had questions. In a few instances, Hammond did the lettering on headstones he had not shaped himself, usually marble ones in an old design which are now badly weathered. Even discounting the weathering, these marble stones are lifeless compared to the ones he made from start to finish using local stone.

He quarried his own rock from a large outcropping of greenstone (known as Sam’s Creek metabasalt) near the intersection of Roop and Buffalo Roads at the western edge of Carroll County. He then sawed it into slabs and smoothed the surfaces before he began carving. According to old maps, there was a sawmill located close to his rock source. Perhaps Hammond used equipment from the mill to cut the slabs. It is unlikely he could have produced tombstones of such large size and uniform thickness using hand tools alone. Boss always had access to horses, which would have been vital for hauling around massive stones.

Hammond laid out his tombstones with an artist’s sense of balance between bold lettering and delicate designs. The border around the edges of the stone served to frame the rest of the carving. He chiseled his letters deep into the stone giving them a superb three- dimensional quality and assuring they would survive centuries of weathering. In raking sunlight, the word “SACRED” on the top of many stones became a very dramatic feature. He often added decorative motifs, but even the stones with only lettering and a border were elegant in their simplicity. During this period, other carvers often decorated their tombstones with weeping willows, urns, or mourning figures, but none of these images appears on Hammond’s work. In studying his stones, one appreciates his firm control over mallet and chisel as well as his understanding of the rock he was cutting. After days of preliminary shaping and polishing, he must have looked forward to the moment he could position a chisel and strike the first mallet blow. The bold, vigorous style of his carving may well have been a reflection of the carver himself.

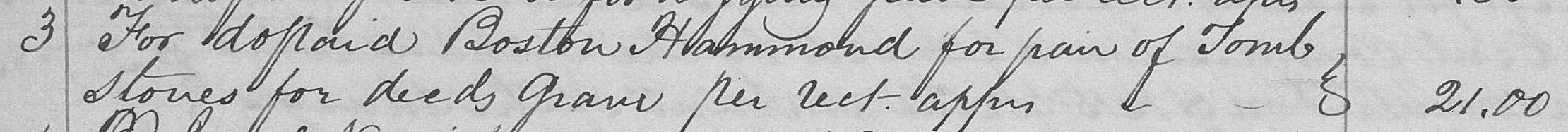

As Colonel Thomas Hammond’s bondsman from 1830 until 1839, Boss turned out dozens and dozens of tombstones. The mid-1830s were his most productive years based upon death dates on the stones themselves. Carroll and Frederick County administration records show local families paid him between $10 and $21 for a headstone and footstone— much less if he only did the lettering. Over 110 Hammond headstones have been discovered so far, but fewer than fifteen probate records contain his name, probably because many families waited until after an estate was completely settled to purchase a memorial. With the exception of one tombstone bought for an African American woman by her white estate executor, the others were apparently made for white individuals. When it came time to place markers on the graves of Boss and his wife in the 1890s, someone recycled two of his smaller stones by gouging out the original names and dates, and then carving the new information. In Unionville’s Linganore Methodist Cemetery, there is an interesting monument to Sarah Dorsey who nursed the famous Methodist preacher Francis Asbury through a serious illness in the late eighteenth century. It was erected in 1902, almost ten years after Boss’ death, and is another example of a recycled Hammond tombstone.

Colonel Hammond apparently allowed Boss to keep some (or perhaps all) of the money he was paid because on July 29,1839, Boss was able to purchase his freedom for $700, a price which seems exceptionally high for someone whose age was listed as 38. The manumission doesn’t mention any payment; it only uses the standard phrase that Boss was freed “…for divers good causes and considerations….” The price comes from Boss’ obituary published in 1893. Enslaved people were sometimes manumitted without any payment, especially as they neared the end of their working years. However, when manumitting a bondsperson, the master essentially guaranteed he was freeing someone who was still “…able to work and gain sufficient livelihood….” This clause presumably prevented owners from releasing enslaved people who would soon be unable to support themselves and become burdens on the community. History proved that Boss Hammond enjoyed many productive years after his release in 1839. The day he became free, he sold two horses to his former enslaver for $107—a transaction recorded in the Frederick County land records. One gets the impression that Colonel Hammond may have struck a hard bargain in setting a high price for freedom, but he was willing to help Boss in various other ways.

For the next eighteen years, Hammond continued to produce tombstones, although his output dwindled during the 1840s and no stones have been found dated after 1857. Prosperous farm families from eastern Frederick and western Carroll Counties were his usual customers; their names—Devilbiss, Baile, Dudderer, Warfield, Greenwood, Bennett, Cassell, and Franklin—are intertwined with that region’s history. Most of the stones are in graveyards along the Carroll- Frederick County border, some reached cemeteries as far away as Frederick City, Woodsboro, and Westminster, while two were recently found in the interesting old Middletown Union Cemetery in northwestern Baltimore County.

In the autumn of 1840, one year after being freed, Hammond purchased his first land—nine acres straddling Buffalo Road, the boundary between Carroll and Frederick Counties. It was part of the large tract known as “Leigh Castle.” The census that year included Boss, his wife, and several children all under the heading of “free colored persons,” although technically Boss may have been the only one who was free. There is some evidence he lived and worked on this land before actually buying it. Two tombstones dated 1834 and 1835 were unearthed there in 2002. The ground was strewn with large slabs of sawn stone suggesting the tombstones had been left at the spot where they were made. Hammond’s home was located on the west side of Buffalo Road in Frederick County, but some outbuildings apparently were built on the Carroll County side. Nothing remains now except a few crumbling foundations and memories among whites and African Americans living in the vicinity. One resident recalled seeing a massive stone chimney that once stood by the road but disappeared during highway improvements. At first the chimney was assumed to be part of the house, but an early twentieth century deed described a limekiln in the same general location. Boss Hammond and Isaac Dotson were two of the earliest black landowners in the area. Their names appear on the 1858 Bond map of Frederick County. Other black families such as the Frances, Hills, Toops, and Cooks also acquired land in what became the small community known as Newport. Black families worshipped alongside white families at nearby Bethel Methodist Church during the first part of the nineteenth century until they established their own Methodist church, Fairview, on Liberty Road.

By 1850 Hammond had amassed seventy acres of land along the Carroll-Frederick border and had improved the majority of it. The Frederick County census taker recorded his real property value at $700. According to a Liberty District agricultural survey made the same year, his livestock included cows, horses, and pigs worth nearly $200. During the previous year he had raised 500 pounds of tobacco plus sizeable quantities of wheat and oats, and he had made 150 pounds of butter. The census taker listed Hammond’s occupation as “stonecutter” although obviously much of his time was spent farming, probably with the help of his two older sons.

Throughout the middle of the century, Boss’ name appears alongside those of neighboring white farmers and tradesmen—buying, selling, or mortgaging land, using the services of the local doctors, and owing small debts to someone’s estate. Documents usually referred to him as “Boss” Hammond during this period,

but occasionally the name was written “Boston” or “Bostion.” In later years “Sebastian” was the name used on census records and deeds and was the name inscribed on his tombstone.

Early in 1856, Nathan Harris Owings of Frederick County manumitted Boss Hammond’s wife, Marcella, and all the children over the age of thirteen. Their freedom cost another $700. Hammond’s obituary says, “Many years ago he [Boss] purchased his freedom from the late Col. Thomas Hammond, of Frederick county, for seven hundred dollars, and after paying for himself he bought his wife and four children for a like sum.” In this instance, the amount seems remarkably low, if it is accurate, because it actually freed seven people. Marcella was about 41 years-old, two sons were ages 24 and 23, and four daughters ranged in age from 20 to 14. The manumission is very informative because it specifically names each child and gives his or her age, including the five children under thirteen who remained enslaved. Hammond probably paid Owings the money over a long period of time, gradually freeing one family member after another, but the manumissions were all recorded together in 1856. When Boss Hammond sold a sizeable tract of land to Abraham Greenwood in 1853, Marcella’s name also appeared on the deed— a good indication she was free by then. No buyer would have risked signing a contract if one of the sellers was still enslaved. As soon as their manumissions were recorded, the older Hammond children obtained certificates of freedom at the Frederick courthouse to use when they traveled away from home. The certificates were intended to prevent free Blacks from being illegally seized and sold into slavery by unscrupulous individuals who sometimes roamed the countryside.

The lives of free Black people were difficult and uncertain much of the time, but in late 1856, Hammond and his wife faced additional worries. Nathan Owings, who still enslaved their fiveyoungest children and one grandchild, was planning to move to Missouri. Boss Hammond had just completed buying the freedom of seven members of his family and now he desperately needed to free six more. No doubt he was aware Missouri was a slave state, so Owings could legally take the children with him or sell them to anyone anywhere before he left. In January 1857, records show Hammond mortgaged six parcels of land, most of what he owned, to George W. Dudderar in return for a loan of $834; Dudderar allowed him five years to repay the loan plus interest at six per cent. No records have been found showing how that money was spent, but when Owings later moved to Missouri, the youngest Hammond children stayed behind. Boss and Marcella Hammond were able to keep their entire family together at a time when many of Maryland’s enslaved families were not so fortunate.

From this time forward, Hammond farmed his land and pursued other occupations such as blacksmithing and lime burning; his days of carving tombstones were behind him. Insights into his agricultural way of life come from several mortgage records of the late 1850s. For collateral, he put up possessions such as pigs, a barn filled with tobacco, a cultivator, a wagon, chairs, bedding and bedsteads, and even a grey horse “with the left eye out.” Ultimately he ceased buying and selling land, probably because of the debt owed to Dudderar which he didn’t repay within the required time. Whatever his financial situation was during the 1860s and 1870s, he was earning a reputation for generosity and fair dealing which lives on among African Americans in the Newport community. As his children married, a number settled nearby. His eldest son, Lloyd, was a Newport merchant and cooper; the two youngest sons were still living at home in 1870, probably helping Boss on the farm. Finally, in 1880, the executors of George Dudderar’s estate demanded repayment of the 1857 loan and Hammond was forced to sell most of his land, although family members purchased some portions. The Democratic Advocate obituary said “He at one time was well off but lost his property and died poor.”

Sebastian Hammond passed away on March 31, 1893, outliving Marcella and several of their children. His Democratic Advocate obituary of April 8, 1893, called him “a worthy colored man” and the American Sentinel, another Carroll County newspaper, said “…the funeral of ‘Boss’ Hammond was very largely attended by both white and colored.” His age at the time of his death is uncertain; the Democratic Advocate listed it as 109, although his headstone in Fairview Cemetery indicates he was 98.

During the century following his death, Hammond and his work were all but forgotten. A few relatives living in the Newport area remembered fragments of his life that had been passed down to them, but no one connected him with the beautiful tombstones standing in so many nearby cemeteries. Today, Sebastian “Boss” Hammond’s reputation is on the rise, just as it was long ago when the talented, hardworking enslaved man began carving his way toward freedom.

Sebastian “Boss” Hammond’s tombstones may be found in Linganore United Methodist Cemetery in Unionville, St. Luke’s (Winter’s) Lutheran Cemetery outside New Windsor, Bethel United Methodist Cemetery near Marston, Pipe Creek Church of the Brethren Cemetery near Uniontown, and in a number of other church and family cemeteries along the Carroll-Frederick County border. The Historical Society of Carroll County, the Historical Society of Frederick County, and the Maryland Historical Society also possess Hammond tombstones in their collections.