On an April morning in 1868, eighteen young African American students filed into a church in Sharpsburg, Maryland, to begin lessons in a new Freedmen’s Bureau school funded by the local African American community. Twelve of the youngsters had been enslaved only four years earlier, before Maryland abolished slavery in 1864. Their teacher, Ezra Johnson, christened the school “American Union.” The church, Tolson’s Chapel, was a small board-and-batten structure which had been built in 1866 on land donated by a Sharpsburg African American couple. Tolson’s Chapel and the American Union school were powerful symbols of what had occurred in this small town only a few years earlier. On September 17, 1862, the Battle of Antietam earned the distinction of the bloodiest single day of fighting during the American Civil War. Almost 23,000 men had been killed, wounded, or reported missing on that horrendous day. The Union Army could claim only a partial victory, but it was enough to give President Abraham Lincoln the opportunity he had awaited to issue the preliminary Emancipation Proclamation on September 22, 1862. A free African American community rose from the sacrifices made on those Sharpsburg fields that September. Although the meaning of the Civil War has been debated ever since the last gun fell silent, the children who entered Tolson’s Chapel on that morning in 1868 symbolized what many felt the war had been all about: freedom.

The Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands, more commonly known as the Freedmen’s Bureau, was created by Congress in 1865 to address issues of reconstruction in the South. The Freedmen’s Bureau operated also in southern Maryland and around the federal capital city. By 1866, the Bureau’s activities had expanded to cover all of Maryland, a result of numerous complaints of unfair and abusive treatment of black Marylanders.

Perhaps the greatest impact the Freedmen’s Bureau had in the mid-Maryland region was its help in the establishment of schools. The Freedmen’s Bureau assisted in the establishment of at least eleven schools in Frederick County, seven in Washington County, and three in Carroll County. The history of the Freedmen’s Bureau school in Sharpsburg is indicative of how these schools were started and operated. Captain J.C. Brubaker of the Freedmen’s Bureau visited Sharpsburg in January and again in March of 1868 to hold meetings about the possibility of opening a school in the town. The Boonsboro Odd Fellow reported in early April of 1868 that Brubaker had been in Boonsboro recently, investigating whether to set up a school there, and had mentioned that the Sharpsburg school would open in April in the African American church. In a letter dated March 28, 1868 from Brubaker to John Kimball, Superintendent of Education for the Freedmen’s Bureau in Washington, D.C. and Maryland, Brubaker reported that he had made arrangements for the teacher for the school in Sharpsburg. “The colored people,” he wrote, “are very anxious to have the school opened and from the spirit manifested I am assured that they will fulfill their part of the contract. I did not have time to arrange for his board but do not think there will be any difficulty.”

Brubaker estimated that about thirty children would attend the day school and as many adults the night school. Three days later, Kimball arranged transportation from Washington, D.C. to Sharpsburg for teacher Ezra A. Johnson. Johnson, who was white, had been teaching in Upper Marlboro, Maryland, but had left because he had been informed by locals that “it was unsafe” for a white man to try and teach a colored school there.

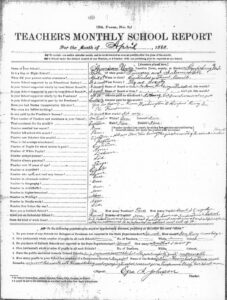

The Sharpsburg Freedmen’s school opened on April 6, 1868, in Tolson’s Chapel. Johnson wrote Kimball that day that he had opened a day school, a night school, a Sabbath school, and that he was going to organize in the coming week “the Vanguard of Freedom,” a temperance organization. He christened the school, “American Union,” and in his first monthly report, stated that he had eighteen students enrolled, evenly divided between male and female. All but three were under the age of sixteen, and only six of the eighteen had been free before the war. On the chapel wall they painted a blackboard of “slating” or “liquid slate” (made with lamp black and shellac) on which to write their lessons. His Sabbath school had attracted twenty-five students. As for public sentiment towards the school, Johnson reported, “In a few cases favorable; but in the great majority, quite unfavorable.” Part of that unfavorable sentiment was directed at Johnson, as he informed Kimball soon after he arrived:

Arrived here safe and sound, but failed to get board with the white people, notwithstanding their having promised the coloured people to give it at a reasonable price. … I am now boarding with one coloured family and lodging with two, until better accommodations can be provided. The fact of the matter is, Mr. Kimble, the citizens would allow a coloured man to teach here, but if possible, they won’t allow a white teacher to come here and teach the coloured people; and they have made up their minds to freeze me out with cold shoulders. But I am too well accustomed to a cold shoulder to allow of that.

The reactions of area residents to the Freedmen’s schools varied, and the teacher at another Washington County school, in Clear Spring, for example, reported that sentiment usually followed political party lines. The reception was different, of course, among the African American community, and Johnson reported to Kimball that his school was entirely funded by the freedmen of Sharpsburg. Johnson’s compensation was $6.50 a month. In May, Johnson had 21 students in attendance, only three of whom had been free before the war, and his Sabbath school continued to be popular, with 40 enrolled. Public sentiment was “generally indifferent,” according to Johnson, which was a slight improvement from April’s “unfavorable.”

Johnson may have been accustomed to a cold shoulder, but by August of 1869, another teacher had taken over the Sharpsburg school – John J. Carter. Carter was a Lincoln University graduate and was supplied by the Presbyterian Committee of Home Missions (PCHM). Carter reported in July 1869 that his summer session had 15 students, and that, “Order is good, moral prospects is somewhat encouraging.” In August, Carter had twenty-five students, and predicted he would have thirty-five to forty in the fall and winter. “They learn very fast,” wrote Carter in his report. The PCHM paid the Tolson’s Chapel trustees ten dollars per month for the use of the church building as a school.

Congress discontinued the Freedmen’s Bureau in 1870, but the African American community in Sharpsburg kept the Tolson’s Chapel school operating until 1899, when Washington County finally took over and built a school for African American children in Sharpsburg.

*See a video about Tolson’s Chapel in the “Video, Maps, Images” section of the website.