The soldiers marching through Baltimore knew they were in trouble. An angry mob had set up barricades to block their path, and rocks, bricks, and other missiles were being hurled at them. The march quickly became a running battle between these young men from Massachusetts and citizens of Baltimore who were infuriated by their presence. At one point shots rang out, and by the time the melee ended, four of the soldiers and at least eleven civilians were dead. On this nineteenth day of April, 1861, the Civil War turned deadly.

The war had actually begun seven days earlier, when Confederates fired on Fort Sumter on April 12, 1861. The Union garrison in the fort surrendered the following day, and miraculously, after thirty-four straight hours of bombardment, not a single soldier had been killed. President Abraham Lincoln called for volunteers to join the military and put a quick end to the rebellion. The first armed volunteers to heed Lincoln’s call came from Massachusetts. The 6th Massachusetts Volunteer Militia left Boston for Washington on April 17 and arrived in Baltimore on the morning of April 19. Several railroad lines converged in Baltimore, but,due to fire hazards, the city did not allow locomotives to operate in the city. To change trains, passengers boarded horse-drawn cars and were pulled on rails between stations. The Massachusetts troops came into the President Street station from the north, and began boarding cars for the Camden station, a little more than a mile away, to continue the trip to Washington. The soldiers had been warned that the city was a hotbed of Southern sympathizers and to expect trouble. They had been ordered to load their rifles before arriving in Baltimore. Most of the soldiers were able to make the trip to the Camden station even though an angry mob hurled rocks and bricks at the cars. Before the final militia companies were able to leave the President Street station, however, the crowd managed to block the city tracks and prevent the horse-drawn cars from advancing. The Massachusetts soldiers were ordered to line up in formation and march to the Camden station. Accounts vary as to what exactly happened during the march, but by the time the soldiers reached safety, fifteen men had been killed.

One of the soldiers killed in Baltimore was Luther Ladd, seventeen years old and from Lowell, Massachusetts. During the riot, Ladd first received a blow to the head, which fractured his skull, and was then shot in the thigh. The ball severed an artery and Ladd bled to death. The last words Ladd is alleged to have said as he died were, “All hail to the Stars and Stripes!” The popular journal Harper’s Weekly called Ladd “the first victim of the war,” although no one is absolutely sure which of the victims died first.

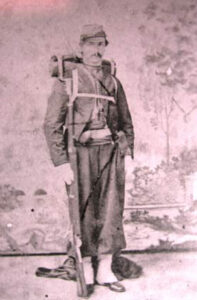

Who killed Ladd, the anointed “first victim of the war”? Several sources attribute the slaying to Dewitt Clinton Rench of Williamsport, in Washington County. Rench (sometimes spelled Rentch) was avidly pro-Southern in his words and actions, and, while in Baltimore studying the law with his uncle, he had joined a Baltimore militia unit. After the trouble in that city, he returned home to live with his father in Williamsport. In June 1861, according to an article from the Williamsport Ledger reprinted in Hagerstown’s the Herald of Freedom and Torch Light, Clinton had “openly boasted that he was in the late Baltimore riot; that he had killed one Massachusetts soldier, and had swung his slung-shots around the heads of some others.” In a history of the 6th Massachusetts Volunteer Militia, published in 1866, the author claimed that Rench “often boasted of the deed, and rejoiced in having killed that ‘boy soldier who shouted for the Stars and Stripes when he fell.’” Rench was mentioned in area newspapers because he himself was killed in Williamsport on June 5, 1861. Most citizens of Williamsport supported the Union, and when Rench rode into town one day, several townspeople warned him to leave. According to the newspaper accounts, Rench was suspected of being a spy and potential recruit for the Confederates camped just across the Potomac. Again, accounts differ as to who fired first, but there was an altercation between Rench and the townspeople and Rench was shot and killed.

Rench’s alleged killing of Luther Ladd and his own death by the hands of his fellow townsmen in Williamsport tragically epitomize the divisiveness of the war in Maryland. The bitterness, anger, and fear caused by these divided loyalties were expressed in a letter Rench’s cousin in nearby Sharpsburg wrote after his death:

Oh my, I did not know I had so much gall in my nature until this war question was brought up and when one of these Union shirkers murdered our dear cousin. Dear sister, I shudder now at my feelings then. I hated my most intimate friends because they were in favor of the Union, right or wrong.