By 1860, following John Brown’s failed attempt at insurrection in Harpers Ferry in 1859, many of the enslaved people below the Mason-Dixon Line believed their fate was in their own hands. Their answers lay not in the laws and justice of the white majority, but in a number of self-propelled routes to freedom. The Underground Railroad was perhaps the most invaluable aid to individuals on the road to freedom, while a few chose the ultimate freedom in death by suicide. Some enslaved individuals were able to save money earned outside of their bound duties to purchase their freedom and that of their loved ones. With the events of the Civil War, several new avenues opened to freedom seekers: escape to safety behind Federal lines or, beginning in 1863, enlistment in the US army. For those already free, the war brought the threat of capture by invading Confederate troops, but also entrepreneurial opportunities providing supplies and services to the army encampments ever-present in the mid-Maryland region.

Escape

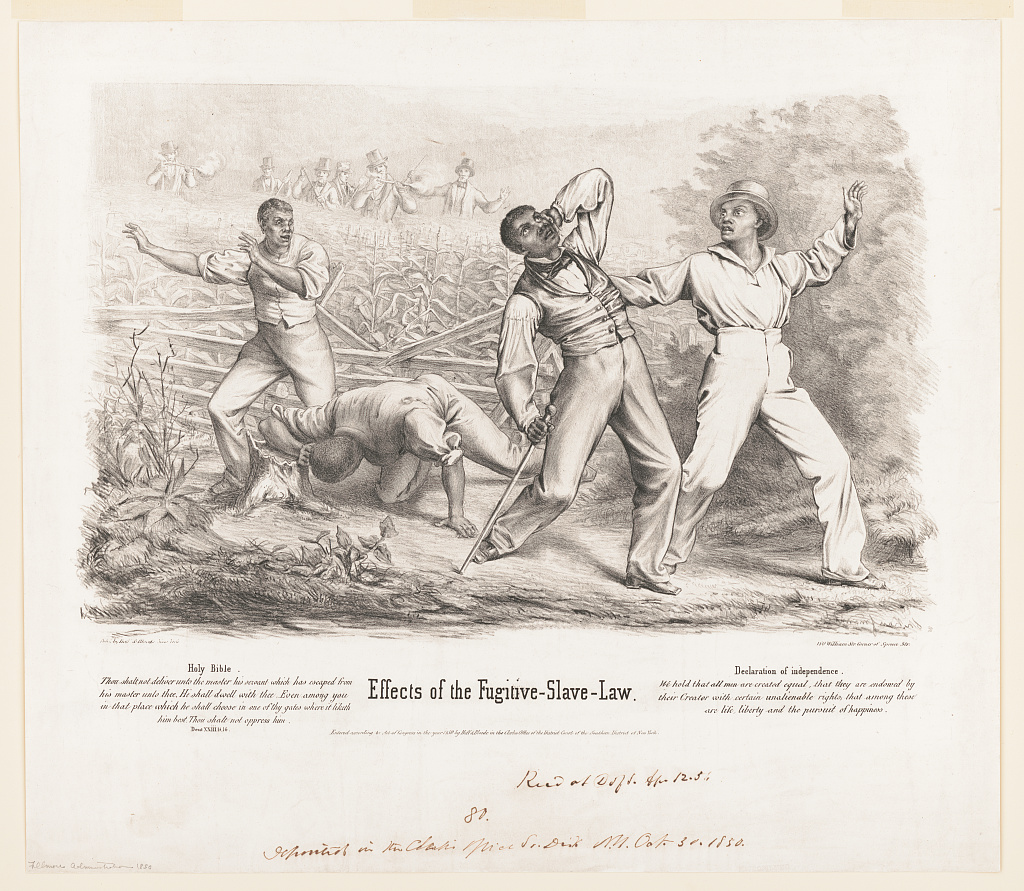

By 1860, the Underground Railroad had helped thousands of freedom seekers to their destinations. But the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 made even the northern free states risky for them. Canada thus became the preferred objective. Rev. William M. Mitchell, an operative in Ohio, wrote in 1860 that “we convey 1,200 Slaves annually to Canada.” William Still’s biographer described the “almost daily” arrival of freedom seekers bound for Canada at his Philadelphia home throughout “the last decade of slavery.” Among those who passed through Still’s station in 1860 were Evan Graff, his brothers Grafton and Allen, Ruth Ann Dorsey, and Isaac Hanson, all from northeastern Frederick County, and David Snively, of Frederick City, who escaped enslaver Charles Preston.

The Civil War provided new opportunities for freedom seekers. Peter Booker and Charles Turner tried a new twist on the old escape plan, wearing army uniforms and claiming to be soldiers in 1862. Carroll County Sheriff Jeremiah Babylon caught the two freedom seekers and held them in the Westminster jail, clearly not convinced by their story. Others took advantage of the disruptions wrought by war. In March 1862, during Confederate General “Stonewall” Jackson’s Shenandoah Valley campaign, a Hagerstown newspaper reported “as many as two thousand fugitive slaves from the Valley of Virginia have crossed the Potomac within the last ten days,” the result of “the rebellion inaugurated by the Cotton states.”

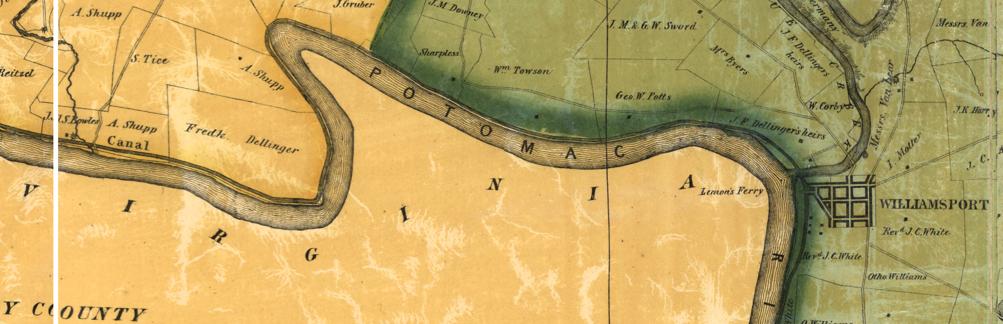

Perhaps the most common plan for freedom seekers during the war was to take shelter among the Federal troops located in Virginia, Maryland, and the District of Columbia. The presence of the US capital at the center of the Potomac region shaped the physical and political landscape of the region during the Civil War. Following Virginia’s vote to secede from the United States, the Federal government moved to protect the capital city of Washington along its southern Potomac border. A series of forts and defensive works were constructed from below Alexandria through Fairfax County, establishing a permanent Union presence within Confederate Virginia territory. At the same time, the government took steps to ensure that Maryland would remain within the Union by preventing secessionist representatives from voting in the crucial secession vote. The ring of US forts and defenses encircled the Federal City on the Maryland side of the river as well, primarily located within the District of Columbia boundaries, but a few installations extended into Maryland’s Montgomery and Prince George’s counties.

Two vital Union transportation routes also ran through Maryland and part of Virginia – the Baltimore & Ohio (B&O) Railroad and the Chesapeake & Ohio (C&O) Canal. The C&O Canal occupied the Maryland side of the Potomac River, running from Georgetown to Cumberland in Allegany County, Maryland. The B&O Railroad proceeded from Baltimore, past Frederick, to Weverton at the southern tip of Washington County, Maryland. There it crossed into Virginia at Harpers Ferry and continued to Martinsburg before crossing the river back into Maryland and continuing to Cumberland and beyond. The strategic value of the railroad and canal ensured a strong Union presence along the Potomac River which formed the Maryland-Virginia border.

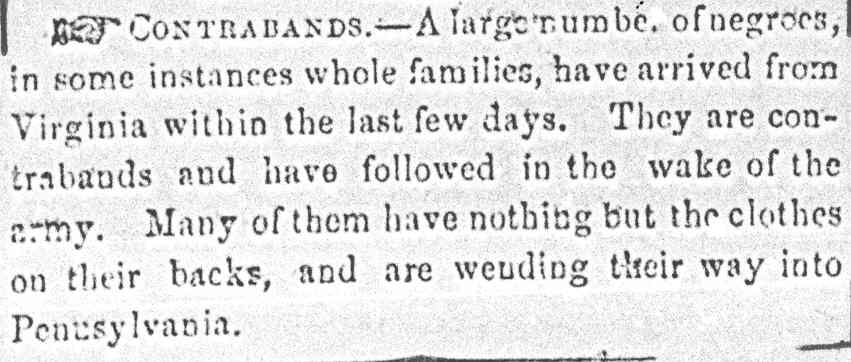

Though President Lincoln assured enslavers that the federal government was not seeking to end slavery, the enslaved people of Maryland and Virginia knew that as soon as Union troops appeared, freedom was within their grasp. “As the first federal troops made their way through Maryland en route to Washington in April 1861,” notes Fields, “slaves begged to be taken along.” In Virginia, three enslaved men sought freedom within the Federal line at Fort Monroe, where General Benjamin F. Butler declared them “contraband of war” and refused to return them to their “owners.” By July there were nearly 1,000 freedom seekers in the camp at Fort Monroe. By August 1861, Congress passed the Confiscation Act, which formalized the government’s right to retain “any person claimed to be held to labor” if their labor was used “against the Government.” The Second Confiscation Act, which passed in July 1862, declared the “contraband of war” to be free. The area inside Washington’s ring of forts quickly became a haven for African American freedom seekers.

In March 1862, Congress enacted an “Additional Act of War” which protected all African American freedom seekers who found their way to Federal lines, forbidding their return to “any persons to whom such service or labor is claimed to be due.” US troops protecting the B&O Railroad in Harpers Ferry, Martinsburg, and Maryland became magnets for self- emancipating bondsmen. Congress followed in April with the abolition of slavery in the District of Columbia. From Sharpsburg in Washington County, Maryland, Savilla Miller wrote to her sister in Iowa in 1862: “Sunday night…old black Sam walked off….[They go] to Martinsburg…[to] get on the cars and go to Washington City, then they are free.” A Frederick County newspaper reported in March 1862 that the, “train from Harpers Ferry last Friday evening brought to Frederick 64 contraband slaves. They are to be sent to Washington to be employed in the Commissary department.” By October 1862, Julia Wilbur, a relief worker for the Rochester Ladies Anti-Slavery Society, found hundreds of women and children in the “contraband camp” outside of Washington known as Camp Barker and five hundred to a thousand in Alexandria.

In a June 1863 report, the American Freedmen’s Inquiry Commission suggested that “negro laborers” should replace large number of white soldiers assigned to duties performed for the “quartermaster’s and commissary departments”:

…on fatigue duty at the various headquarters, on pioneer service &c., and that on marches, where guards for the trains, parties for cutting roads, building bridges, and similar labor are required, the number is much greater. If there be included the labor on intrenchments and fortifications, on garrison duty, in ambulance corps, in hospitals, as guides, and spies, &c., it will, the Commission believe, be found that one-eighth might be added to the available strength of our armies by employing negroes in services other than actual warfare. The commission estimated 100,000 laborers could be added to the ranks by employing Black men, noting the work “would be better performed by them than by white men detailed from the ranks; for all experienced officers know how difficult it is to obtain labor from soldiers outside of the ordinary routine of their duties.”

While many enslaved people in the region were attempting to obtain freedom, free African Americans feared the prospect of enslavement. In June 1863, during the Confederate invasion of Pennsylvania, Black men, women, and children were kidnapped by Confederate soldiers and taken south to be sold as slaves. Charles Hartman, a resident of Greencastle, Pennsylvania, just a few miles north of the Maryland border, observed the men of Confederate General Jenkins’ cavalry plundering area farms for stores, livestock, and African Americans:

One of the exciting features of the day was the scouring of the fields about town and searching of houses for negroes. These poor creatures, those of them who had not fled upon the approach of the foe, concealed in wheat fields about the town. Cavalry men rode in search of them and many of them were caught after a desperate chase and being fired at.

A similar scene occurred in Chambersburg where 30 to 40 Black women and children were captured for sale in the South. Later, Greencastle residents rallied to rescue the prisoners, the story recounted in an article published in the Chambersburg newspaper Repository:

Quite a number of negroes, free and slave – men, women, and children – were captured by Jenkins and started South to be sold into bondage. Many escaped in various ways, and the people of Greencastle captured the guard of one negro train and discharged the negroes; but, perhaps, full fifty were got off to slavery.

As the cavalry left town with their plunder, the children were reportedly “mounted in front or behind the rebels on their horses,” presumably as human shields to protect their escape.

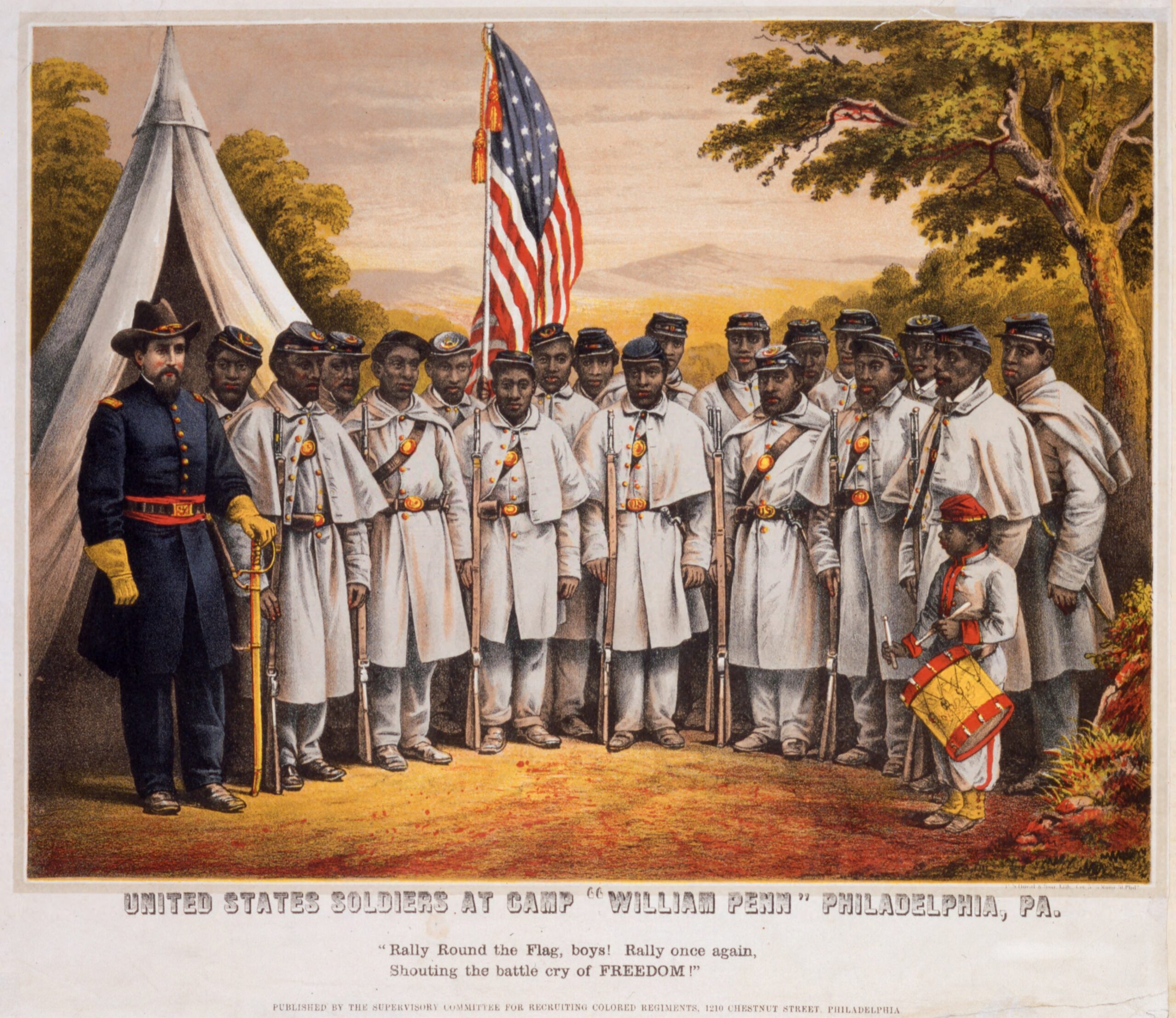

Enlist

On July 17, 1862, Congress passed the Second Confiscation and Militia Act, authorizing African Americans to serve in the US Army. African Americans could now serve in the army in any capacity that President Abraham Lincoln deemed “best for the public welfare,” but he was not yet ready to allow their use in combat.

The Emancipation Proclamation in January 1863 changed that. In late January 1863, Massachusetts began recruiting free African American men, forming the 54th Massachusetts Regiment. So many men volunteered that another regiment, the 55th, was also organized. A recruiter for the 54th must have targeted south-central Pennsylvania because forty-three men from Franklin County alone joined the 54th, including four brothers from the Christy family of Mercersburg and three of their brothers-in-law.

The recruitment of African American soldiers in mid-Maryland was hugely successful through the summer 1863 with as many as 200 men enlisted just from the border area of Frederick and Carroll counties, 70-80 from the Clear Spring district in Washington County, while 40 men – “including a negro brass band” called the Moxley Band – reported from Hagerstown. Some Maryland enslavers claimed, however, that enlistment officers were illegally recruiting enslaved men. On March 21, 1863, Col. Robert Creager was arrested for “enticing slaves to escape from their owners,” after visiting an “African church” in Frederick where he recruited “50 or 60 negroes, among them several slaves.”

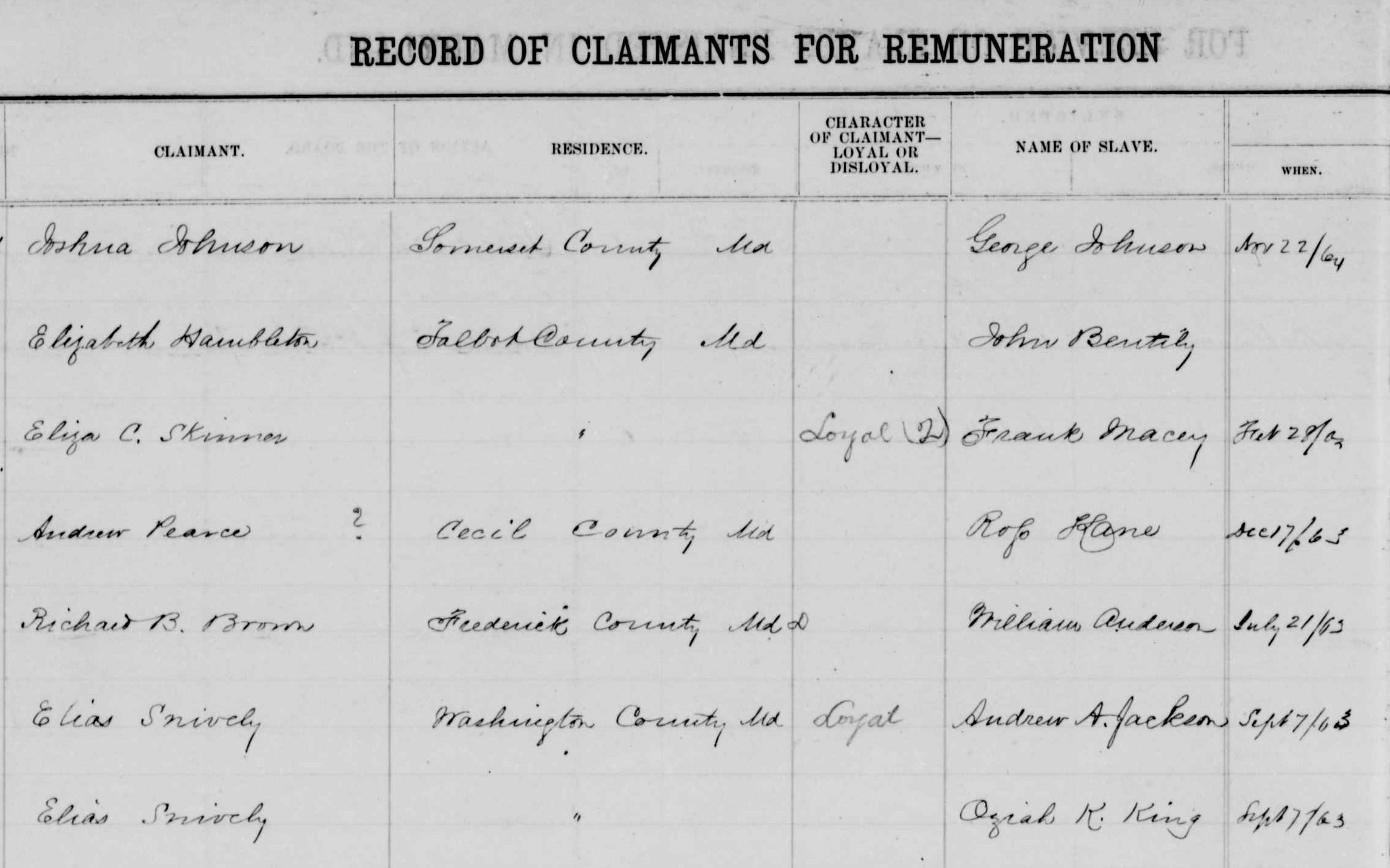

In general, however, recruitment elsewhere proved slow. In October 1863 the War Department issued General Order 329 providing “for enlistment of free blacks, slaves of disloyal owners, and slaves of consenting loyal owners in the border states.” Section 6 of the order stated that if any citizen should offer his or her slave for enlistment into the military service, that person would, “if such slave be accepted, receive from the recruiting officer a certificate thereof, and become entitled to compensation for the service or labor of said slave, not exceeding the sum of three hundred dollars, upon filing a valid deed of manumission and of release, and making satisfactory proof of title.”

Enslaved men enlisted in the US army in this way would be free men as a result of their service. Enslavers loyal to the United States were entitled to compensation for the enlistment of their enslaved men, and some in Maryland viewed this as their last opportunity to receive payment for the loss of their “property.” Twenty such enslavers in Washington County claimed compensation for the enlistment of 27 slaves. A list of drafted men from two districts in Frederick County included six enslaved men. In an ironic twist at the final battle for Richmond in April 1865, Jesse Downey and Ignatius Dorsey, two landowners from Frederick County serving in the Confederate 1st Maryland Regiment, faced their former bondsmen John Williams and Lewis Wineberry, soldiers in the United States Colored Troops (USCT).

Others were not so eager to send their bondsmen to war. John Otto of Sharpsburg paid the $300 bounty to release his enslaved man Hilary Watson from the draft. Henry Piper, also of Sharpsburg, was similarly determined to protect Jeremiah Summers, who was born enslaved on the Piper farm. In April 1864, a company of USCT arrived in Sharpsburg and set up a recruitment office in the local Methodist Church. Led by Captains Holsinger and Fletcher, they began enlisting local African Americans. Piper claimed that some were taken illegally:

…that day, divers colored men, free and slave, were seized and taken to the Quarters aforesaid, among them, “Jeremiah Summers,” colored boy owned and possessed by Henry Piper of said Town. Said boy being about 16 years and 9 months old, he Summers by reason of his minority, never having been enrolled, and hence no way liable to Military duty.

Although Piper, a staunch US loyalist, protested the seizure of Summers, the young man and the others were moved from Sharpsburg. Local citizens petitioned General Lew Wallace, then commanding the Middle Department, US Army, in Baltimore and Summers was returned to the Piper farm.

Simply being allowed into the army was only the first hurdle experienced by African Americans who were willing to fight and die for the United States. Racism infected all sectors of American society in the nineteenth century, and many white US officers and soldiers disparaged the abilities of the new recruits. African American soldiers were subjected to unequal pay, menial duties, dilapidated barracks, derision by many fellow soldiers, and a reluctance to allow them in actual combat. Jacob Christy, from Mercersburg, Pennsylvania and a member of the 54th Massachusetts Regiment, expressed frustration in a letter to his sister about African American soldiers not receiving pay, and spoke of his determination to fight for the rights of African Americans:

We have been fighting as brave as ever [thay?] was any soldiers fought[.] I know if every regiment that are out and have been out would have dun as well as we have the war would be over[.] I du really think that its God will that this [war] Shall not end till the Colord people get thier rights[.] [I]t goes verry hard for the White people to think of it But by gods will and powr thay will have thier rights[.] [U]s that are liveing [now] may not live to see it[.] I shall die a trying for our rights so that other that are born hereaffter may live and enjoy a happy life[.]

The US Army’s seemingly insatiable need for men proved greater than racism, however, and the new African American units were finally thrust into battle, albeit in segregated units called the United States Colored Troops (USCT). For the final two years of the war, these men proved their valor. USCT units fought in all theaters of the war, and according to one historian, participated in almost 450 military engagements, 39 of which were major battles. Twenty-three African American soldiers were awarded the Medal of Honor.

In Maryland, even though the War Department’s orders of October 1863 had established two recruiting stations in mid-Maryland – at Hagerstown and Monocacy Junction – for African Americans who wanted to join the US army, the local provost marshal’s office was slow in figuring out how to proceed with the enlistment of Black soldiers. In January 1864, Provost Marshal James Smith wrote to his superior in Baltimore, N.L. Jeffries, the Provost Marshal of Maryland, asking, “Shall I use my efforts to enlist negroes? Shall I swear and muster them in? Numbers of them might be got in this District.” Smith had been asked about black recruits several months before by his Deputy Provost Marshal in Washington County, F. Dorsy Herbert, who had written in a letter to Smith:

If a company of colored men should be raised will they be accepted and mustered into service? A gentleman by the name of Prather who resides in Clearspring informs me that he can enlist a company in that vicinity before the draft comes off – provided they will be accepted, and that he will take command of the company.

Smith again asked his commanding officer for instructions in February 1864, as more and more African Americans desired to enlist.

I am interrogated every day in relation to the enlistment of negroes, by whom they are to be recruited? What bounty is to be given? And what pay promised them? Those people are going off every day to Pa. and yet all is uncertainty and inaction here. My understanding of the matter is that I am not expected to recruit colored men at all, and I so inform persons who apply to me on that subject. It seems to me that the two classes, white and black, ought to be enlisted separately and by different officers. Be that as it may, no person here seems authorized to enlist them, and they go away and are lost to the State.

Smith’s fears of losing Black recruits were further confirmed the day after writing Jeffries, in a letter he received from B.F. Kendall, the new Deputy Provost Marshal for Washington County. “It has been suggested to me this evening,” wrote Kendall, “that some effort ought to be made to secure by enlistment as many of our free Negroes as possible for the army – it is believed secret agents are here offering them inducements to enter regiments from Northern States.” Kendall added, “We are all very anxious to see recruiting commenced.” Smith himself had written to Jeffries a month earlier telling him that the irrepressible Colonel Creager, now out of jail, was in the area recruiting African American soldiers for northern states. Smith wrote that he had directed the arrest of anyone enlisting men at Hagerstown for northern states.

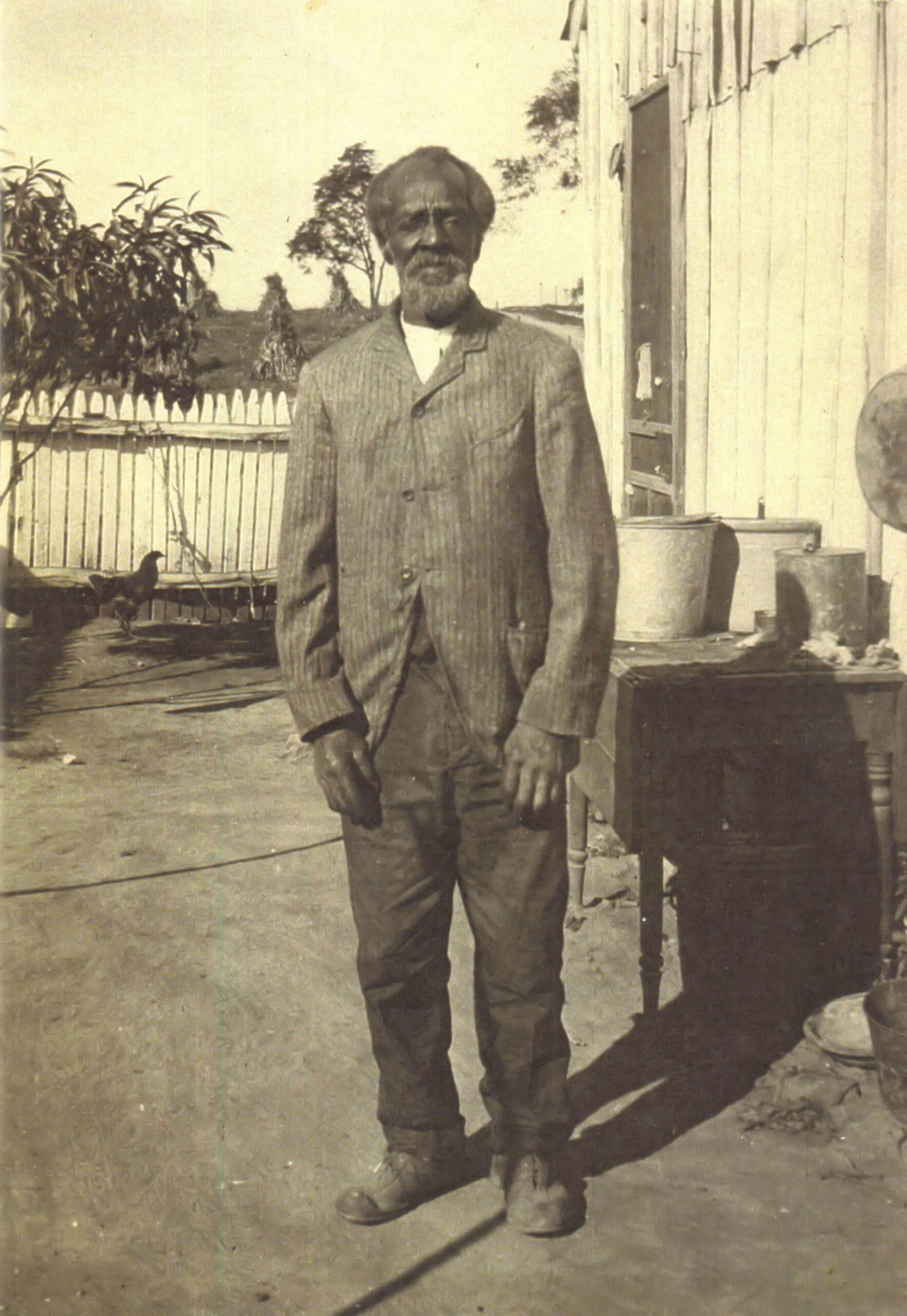

Perhaps the most famous African American soldier from the region was Decatur Dorsey. Dorsey was born c.1836 near New London in Frederick County. He had been enslaved as a young man, although it is unclear whether he was enslaved at the time of his enlistment. Dorsey enrolled in Company B of the 39th Regiment of the USCT in March 1864 in Baltimore. In May he was promoted to corporal and then by July, to sergeant. The 39th Regiment participated in many of the battles in Virginia in 1864, including the Wilderness Campaign and General U.S. Grant’s march to the James River and on to the siege of Petersburg.

From the summer of 1864 until the spring of 1865, Federal forces kept the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia bottled up around Petersburg, Virginia. In an early attempt to break through the Confederate strong defensive lines, US Army engineers in July 1864 dug a tunnel from the Federal lines to beneath a section of the Confederate fortifications, and packed explosives in the tunnel. On July 30, the engineers exploded the charges, which produced many Confederate casualties and a huge crater in the Confederate lines. US forces, led by USCT units, charged the

Confederates, taking advantage of the panic and confusion caused by the explosion. But poor leadership and a quick recovery by Confederate reinforcements spelled disaster for the Federal units, who were mowed down as they converged in and around the crater site. Units of the USCT, especially Dorsey’s regiment, were the first to be sent into the crater, and these units suffered heavy casualties. Many of the African American soldiers who participated in the battle were praised for their bravery, however, especially Sergeant Decatur Dorsey. Dorsey was the color bearer for his regiment that day, and was later awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor for his actions at Petersburg. The official citation reads: “Planted his colors on the Confederate works in advance of his regiment, and when the regiment was driven back to the Union works he carried the colors there and bravely rallied the men.”

For the state as a whole, by the war’s end, over 8,700 African Americans from Maryland had enlisted for the Union. Almost 900 of these soldiers came from Carroll, Frederick, and Washington counties, and at least 156 of these had been enslaved before enlistment.

Entrench

While many free and enslaved African Americans chose to leave the area and move further north, especially during the three Confederate invasions of the region, others took advantage of the new economic opportunities presented by the war. Some became teamsters for the US Army or sold produce and other items to the ever-present encampments of soldiers. One soldier in Williamsport, in Washington County, remarked in a letter that his fellow soldiers all bought milk from a local African American woman and that she also washed clothes for the men. Nathan Williams, whose farm included the ruins of Fort Frederick in far western Washington County, sold produce to soldiers on both sides of the Potomac River. Williams reportedly shared information he garnered about Confederate movements with his Union customers.

Others who did not leave the region endured the war by going about their business, and keeping a low profile. Benjamin Tucker Tanner served as the minister of Quinn’s Chapel in Frederick during the latter half of the war, and his son, Henry Ossawa Tanner, later wrote about his memories of the family’s wartime experiences. “From our attic window the rebel camp and soldiers could be seen. Once my father for some cause was at the [church] and by his clothes was recognized as a minister. ‘Hello!” [said a soldier to his father] “…what are you doing with those duds on, take this,’ and he was kicked out of the [church]. I believe my father said he was drunk.” Henry also remembered that his father took the precaution of nailing boards over the windows in the house to make it look abandoned, and although rebel soldiers passed by their house all day long, only one stopped to bang on the door, and he was told by an officer to move on.

The war brought additional burdens to African American families. Even in the best of times, African Americans were usually employed in the lowest-paying jobs. When African American men left the region to avoid capture or to fight for the US Army, women had to work that much harder. David Demus, from Mercersburg, fought with the 54th Massachusetts, and letters between Demus and his wife Mary Jane reveal the hardships of surviving the war. In 1863, in reply to a letter from Mary Jane in which she told him she was working in a field husking corn, Demus was upset that she was doing that kind of work and told her she should stop. In another letter, Mary Jane tells her husband that she will have to hire herself out because everything is so expensive and she has to earn money. In March of 1864, Demus wrote to Mary Jane, “[I] am sorry to think how you hafe to get a long[.] [I] never thot that you [would] hafte to Wark so hard to get a long[.]” Part of the problem was that Demus’ pay as a soldier was irregular, and he often complained of not getting paid at all. In April 1864, Demus wrote to his wife that he would get paid soon, and he wanted her to stop working outside the home because he knew that “you Cant stande it mutch longer….” Life was tenuous in the best of times for African Americans, and war made life even more difficult.

A New Beginning

President Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation of January 1863 freed those enslaved in Virginia and the other rebellious states of the South. In reality, those enslaved people were not truly free until the end of the war in April 1865. More importantly, later that year, the passage of the 13th Amendment to the US Constitution officially abolished slavery throughout the United States.

The enslaved people living in the border states of Maryland, Kentucky, Delaware, and Missouri, all slave states still within the Union during the war, were not included in the Emancipation Proclamation. In 1864, the strongly pro-US Unconditional Unionists of Maryland, in control of Maryland’s political machinery at the time, proposed a new state constitution that included a measure to abolish slavery in the state. In a close vote by Maryland’s citizens, the new constitution was approved, and on November 1, 1864, Maryland’s approximately 90,000 enslaved men, women, and children were emancipated, ending a long struggle for freedom and beginning the long road to equality. In one of those odd historical twists of fate, former Frederick City resident Roger Brooke Taney, who as Chief Justice of the US Supreme Court authored the infamous Dred Scott decision ruling African Americans could never become citizens of the United States, passed away on the day Marylanders voted to abolish slavery. Taney is buried in Frederick, only yards away from the grave of George Washington, a veteran of the United States Colored Infantry, who fought for freedom for all African Americans and for their right to become full citizens of the United States.

*For African American experiences after the war, please see the essays in the “Reconstruction” section.

Stories in Focus